Another 250th Anniversary

And How I'll Be Celebrating It

This year marks a special anniversary for Americans as we celebrate the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence and—one hopes—find ourselves reinvigorated by the spirit of liberty and independence expressed in that founding document.

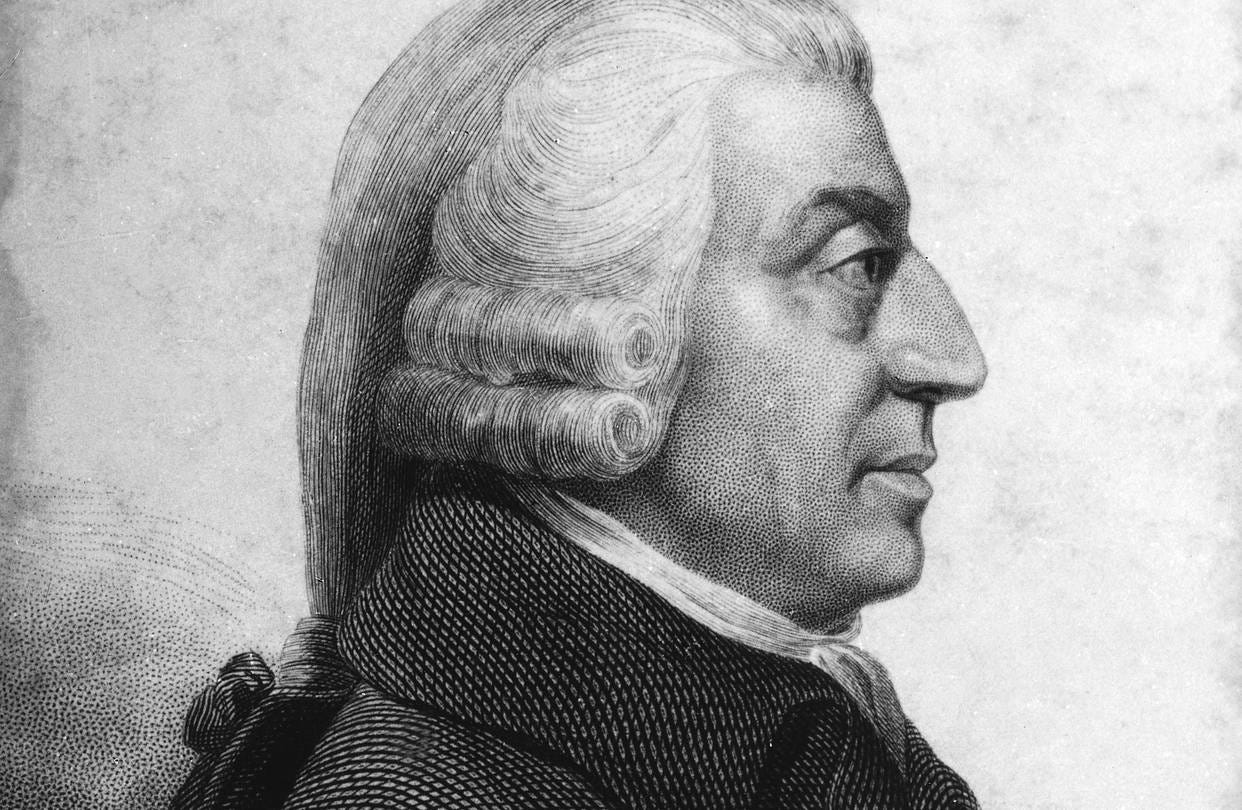

But it also marks 250 years of another treasured text, celebrated by economists worldwide: Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations. In the spirit of that work, I’ve decided to spend part of my semester at George Mason University (GMU) studying the insights of the great Scot in what will, admittedly, be my first time reading his book cover-to-cover.

There is also a more sentimental reason for this decision. During my first visit to GMU as an undergraduate nearly eight years ago, I had the pleasure of meeting two professors in the economics department: the late Walter E. Williams and Don Boudreaux. The photo below was taken after that meeting.

Ever since that meeting, I’ve wanted to study under Professor Boudreaux—which meant, inevitably, taking his course on The Wealth of Nations. It wasn’t until recently that I realized the photo was taken on March 6, 2018—just three days before the March 9 anniversary of The Wealth of Nations’ original publication.

The original structure of the course involved weekly written assignments summarizing each week’s readings, but those assignments were dropped this semester. Nevertheless, to deepen my own engagement with Smith’s text and, I hope, to offer something of value to readers, I’ve decided to write those summaries anyway.

Rather than reciting Smith’s most famous lines or attempting an exhaustive summary (both of which can be found easily online or produced with the help of AI), each week I’ll highlight a handful of ideas that I find particularly insightful, novel, erroneous, or otherwise interesting.

I’ll generally try to write these reflections before each week’s lecture so that the thoughts expressed are my own. Since the first class has already passed, however, I’ll begin by paraphrasing an important point Professor Boudreaux made in his opening remarks.

An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

Professor Boudreaux stressed the full title of the book we would be reading: An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Smith’s work is, quite literally, an inquiry—an open-ended investigation that invites the reader to think alongside him, rather than a rigid lecture or a manifesto of free-market policy, as many of his detractors would suggest.

Smith’s inquiry centers on two related questions: first, what is the nature of the wealth of nations? And second, what is the cause of that wealth?

Wealth, Smith argues, is not an accumulation of gold or specie, as the mercantilists believed. Rather, it was the development of ordinary citizens being able to produce more than is necessary for their immediate survival—made possible through cooperation, specialization, and innovation. In many respects, this condition is unnatural. For most of human history, the norm was abject poverty, subsistence living, and a constant struggle for survival. That this remains the reality in much of the world is difficult for many of us to imagine, but it is nonetheless humanity’s natural state. Understanding the causes of wealth, then, is essential for formulating policies that genuinely promote prosperity.

Adam Smith on the Origins of Money

One of the most surprising discoveries for me was that an entire chapter early in Book I (there are five books total) is devoted to the origins of money. I’ve long been familiar with Carl Menger’s account on the same topic, written more than a century after Smith but had never given much thought to what had inspired it.

In brief, Menger argued that money emerged spontaneously, without central design, as individuals sought to exchange and to overcome the “double coincidence of wants” inherent in barter. I have A, you have B. We might both want to trade A, but I don’t want B. No deal.

Menger’s thoughts on the qualities that make good money, such as durability, divisibility, and homogeneity, always stood out to me as did the historical examples he provided of commodities that once functioned as money such as cowrie shells, cattle, leather, and salt and why those items ultimately fell out of use.

What astonished me was how fully Smith had already anticipated this story. Hinting at the spontaneous emergence of money, Smith writes:

The butcher has more meat in his shop than he himself can consume, and the brewer and the baker would each of them be willing to purchase a part of it. But they have nothing to offer in exchange, except the different productions of their respective trades, and the butcher is already provided with all the bread and beer which he has immediate occasion for. No exchange can, in this case, be made between them. He cannot be their merchant, nor they his customers; and they are all of them thus mutually less serviceable to one another. In order to avoid the inconveniency of such situations, every prudent man in every period of society, after the first establishment of the division of labour, must naturally have endeavoured to manage his affairs in such a manner, as to have at all times by him, besides the peculiar produce of his own industry, a certain quantity of some one commodity or other, such as he imagined few people would be likely to refuse in exchange for the produce of their industry. (emphasis added)

Like Menger, Smith catalogs the wide range of commodities that have historically served as money—cattle, shells, leather, tobacco, sugar, dried cod, even nails. Yet, he observes, “in all countries… men seem at last to have been determined by irresistible reasons to give the preference… to metals above every other commodity.”

He immediately identifies durability and divisibility as decisive advantages:

Metals can not only be kept with as little loss as any other commodity… but they can likewise, without any loss, be divided into any number of parts… a quality which no other equally durable commodities possess.

Smith also recognizes the problems posed by raw metals—namely weighing and assaying—and explains how minting and stamping emerged as solutions, effectively addressing the homogeneity problem emphasized by Menger. After revisiting Menger’s work, I failed to find any novel ideas that were not already present in Smith’s account, though I’m sure they exist.

On Productivity and Labor

My final observation comes from Smith’s Introduction and Plan of the Work which precedes Book I. In that introduction he lays out his basic theory that greater production is the result of two things: first, “the skill, dexterity, and judgement with which its labour is generally applied;” and second, “the proportion between the number of those who are employed in useful labor, and that of those who are not so employed.”

It was predominately the former of these two that mattered in his view:

Among the savage nations of hunters and fishers, every individual who is able to work, is more or less employed in useful labour, and endeavours to provide, as well as he can, the necessaries and conveniencies of life… Such nations, however, are so miserably poor, that from mere want, they are frequently reduced, or, at least, think themselves reduced, to the necessity sometimes of directly destroying, and sometimes of abandoning their infants, their old people, and those afflicted with lingering diseases, to perish with hunger, or to be devoured by wild beasts. Among civilized and thriving nations, on the contrary, though a great number of people do not labour at all, many of whom consume the produce of ten times, frequently of a hundred times more labour than the greater part of those who work; yet the produce of the whole labour of the society is so great, that all are often abundantly supplied, and a workman, even of the lowest and poorest order, if he is frugal and industrious, may enjoy a greater share of the necessaries and conveniencies of life than it is possible for any savage to acquire.

This observation brought to mind debates I’ve heard in Congress, where there is concern over declining labor force participation. Much of that concern focused on the erosion of the perceived value of work—whether due to welfare dependence or broader social changes. There is truth in those concerns, just as there is truth in critiques of labor regulations.

But I believe that what was true in Smith’s day holds in ours: in a growing, wealthy economy, we should not be surprised to see fewer people needing to work, or the people who do work needing to work fewer hours.

Briliant timing on this project. The parallel Smith draws between savage nations using full labor participation versus civilized nations with lower participation yet higher output feels super relevant to today's labor debates. I've been following similar patterns in automation discussions, where people worry about jobs disappearing when historically higher productivity always meant better living standards even with less work. Smith basically predcited this centuries ago.