Carbon Taxes Are More Problematic Than They Seem

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) reports that the government subsidizes fossil fuels, coal, and natural gas by on the order of $700 billion per year. For those familiar with the national budget of the United States, this is approximately equivalent to our annual defense spending, which accounts for around 13% of our total annual expenditure. This is a monstrous amount, and given the state of our fiscal imbalance, it should be adequately addressed and reduced if true. But, if you were to wish to learn more about these data and, as a result, intensely scrutinize the federal balance sheet, you would be unable to find the figure given by the IMF. So then, where does this number come from?

The IMF is accounting for the social cost of carbon emissions produced by these energy generation methods. Per their estimates, by not explicitly taxing these, this acts the same as a subsidy. If one is to ignore this rather dubious accounting methodology, which assumes an objective carbon tax rate, the subsidy rate for fossil fuels and coal is, of course, much lower, being $15.6 billion in 2022.

With this in mind, let’s try to understand what draws people to the carbon tax as a policy. It all started in the 1920s, when economist Arthur Cecil Pigou began to research externalities. Externalities, or spillover effects, are often not accounted for in transactions, leading many exchanges to either be more or less costly to society than a balance sheet may represent. The classic example of this is pollution, and the classic response is to implement something called a Pigouvian tax. Pigouvian taxes are designed to disincentivize people from engaging in socially harmful behaviors. Popularized in the early 2000s, carbon taxes are a specific example of a Pigouvian tax, in that they are designed to tax carbon emissions to prevent them, somewhat, from happening, thus bringing economic output closer to a socially optimal level. It is natural, then, to see a carbon tax as an economically minded policy designed to prevent climate damage. But the deeper one digs into the issue, the less and less attractive carbon taxes become.

Firstly, the basic assumption that there is an optimal carbon tax rate is, quite simply, false. To determine this, one needs to determine the social cost of carbon, which is the cost faced by society from excess carbon emissions. The price society would be willing to pay to remove all pollution could change from region to region and from day to day. Prices, in free markets, are volatile, and to set a specific social cost of carbon would be no different from setting a price control on carbon emissions. Price controls are broadly harmful as they work against natural market mechanisms, creating inefficiencies at worst, and doing nothing at best. From a more empirical perspective, each researcher has his or her own method for estimating the social cost of carbon, which can lead to computations that result in hugely different prescriptions for optimal carbon tax rates.

But take this, for a moment, as a non-issue. Suppose statistical models and computer programs become precise enough that they can account for this problem. Carbon taxes would still have a myriad of problematic results. One of the most prominent issues in the conversation surrounding their implementation is that they are regressive in nature. This means that they disproportionately have greater negative effects on poorer people than wealthier people, as they are a flat tax on carbon emissions, and the wealthy can afford to offset their usage toward other energy generation methods with lower carbon emissions. Take, for example, a tax on emissions from a vehicle. A wealthy person and a poorer person might drive the same, but the percentage of their incomes that they spend on gas varies wildly. The poorer person would spend comparatively a much larger amount on fuel, and thus on the carbon tax, than the richer person, making the policy regressive.

Suppose, too, that this wasn’t an issue. Carbon taxes would still be problematic as they lead to something known as carbon leakage. This is when economic agents notice that carbon is cheaper in another country and expend resources to produce carbon there instead, with hopes of decreasing costs below what they would be by staying and paying for the full carbon tax. Note that for this to happen, the cost of importing only needs to be just below the cost of the carbon tax for it to be economically rational.

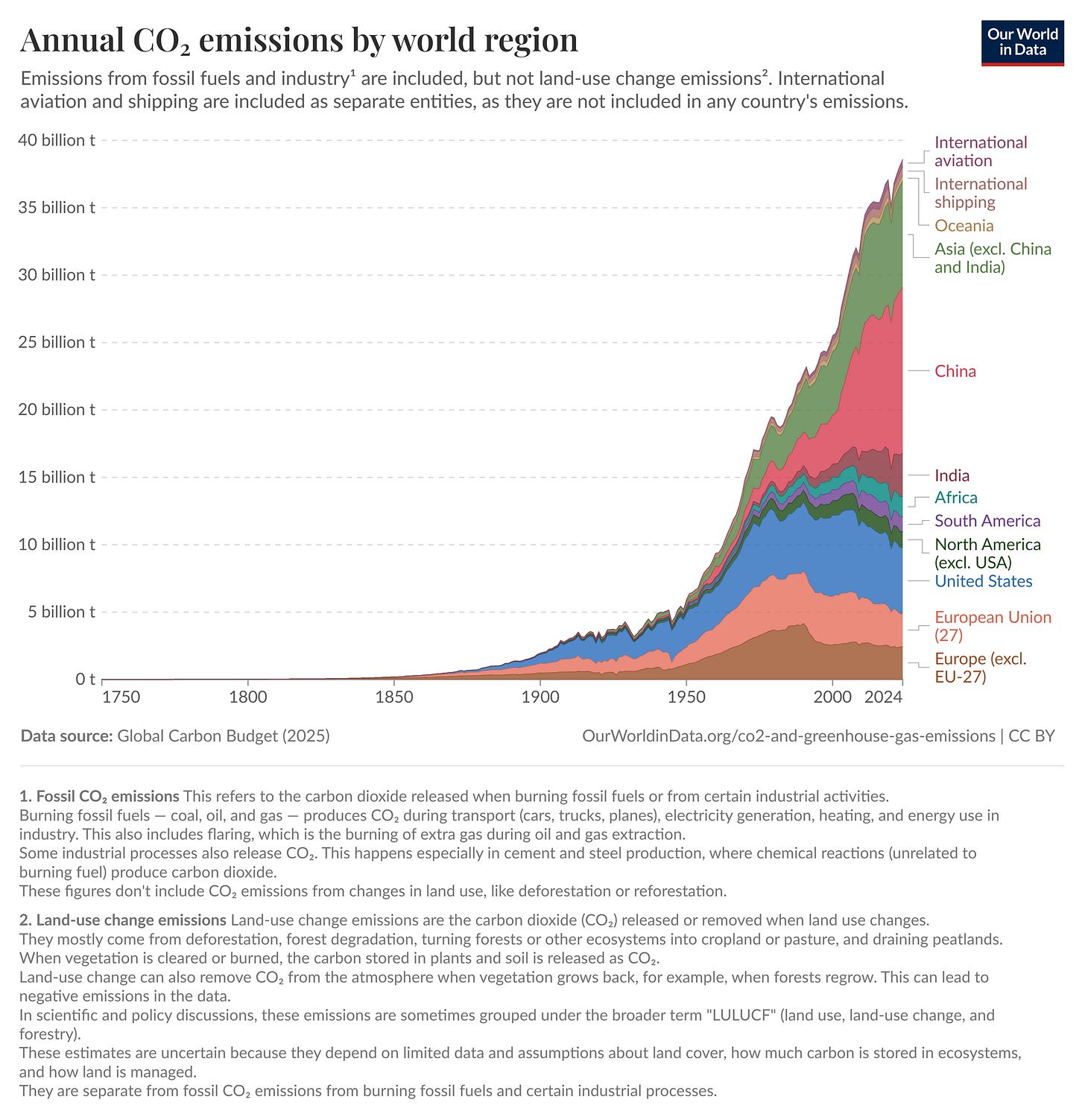

The above graph highlights this, to some extent. Note how the emissions in the West, or the United States and the European Union, are staying the same or trending down as of 2024, while the emissions in China, a country with very few climate laws, are exploding. China is known for its massive manufacturing industry, and while this isn’t a direct result of something so simple as a carbon tax, it does highlight how the rate of overall emissions increases is remaining rather steady due to emission transfers. These transfers happen for a variety of reasons, whether they are due to shifts in comparative advantages that occur naturally or because of policies like carbon taxes that alter the incentives within domestic markets.

With this in mind, the natural result of a carbon tax would be increased domestic energy prices, either because of the price of importing “dirty” energy usage from the third world, or because the economically rational decision is to now produce higher-cost green energy. Additionally, the carbon emissions in foreign markets would also increase, keeping the total global emissions at a relatively unchanged level.

It seems clear, then, that a carbon tax does not solve the issue of carbon emissions, and also creates price distortions and increases similar to what we would expect to see from something like a tariff. So where did Pigou go wrong? It turns out that for this system to work, in which one seeks to internalize this negative externality to achieve the socially optimal level of pollution, one would need to entirely remove the incentive to transfer carbon emissions to nations with less restrictive climate laws. This can be done in a few ways. One would be to place a tax on imports that is equal to what the tax on carbon emissions would be. In this way, domestic markets can essentially establish a carbon tax on foreign goods without needing to have access to foreign tax policy. Another solution would be to have a global carbon tax, but seeing as this would require a global government, this fails to even be in the ballpark of a reasonable remedy.

However, neither of the above solutions to carbon tax avoidance through carbon leakage, which make the situation worse, not better, if implemented, addresses the other problems with a carbon tax. The policy is still regressive, and the social cost of carbon is still arbitrary. Carbon taxes are governmental economic punishments that serve to divert the economy from its natural progression by distorting prices, altering industry, and are not a reasonable method to reduce carbon emissions. At a minimum, proponents must grapple seriously with these limitations before treating carbon taxation as a settled or optimal policy response.

I think that "cost of carbon" is not the best way to think about CO2 accumulation which is a multi-generation, global, general eequilibrium problem whereas "cost of carbon implies a a microeconomic optimization. Distirbution of the costs of taxing net emissoins of CO2, cannot be ignored, but there are distributional consequenses of the CO2 accumulation.