CBO Fiscal Multiplier Assumptions Overstate the Impact of Fiscal Stimulus Spending

A Closer Look at the Assumptions Driving Federal Stimulus Forecasts

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, U.S. policymakers authorized over $5 trillion in fiscal stimulus, relying heavily on projections from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) that promised strong economic returns. The CBO projected that each dollar of federal spending could generate $1.50 in additional economic output — a multiplier large enough that policymakers felt justified in their aggressive deficit-financed interventions.

However, CBO multiplier estimates are deeply flawed. They rest on outdated models, questionable assumptions, and empirical methods that systematically overstate the true economic impact of stimulus spending. A growing body of recent research indicates that the actual multipliers are far lower, often below 1, suggesting that the CBO’s central estimate of 1.5 is analytically weak and potentially misleading for policymaking.

The Source of CBO’s Assumptions

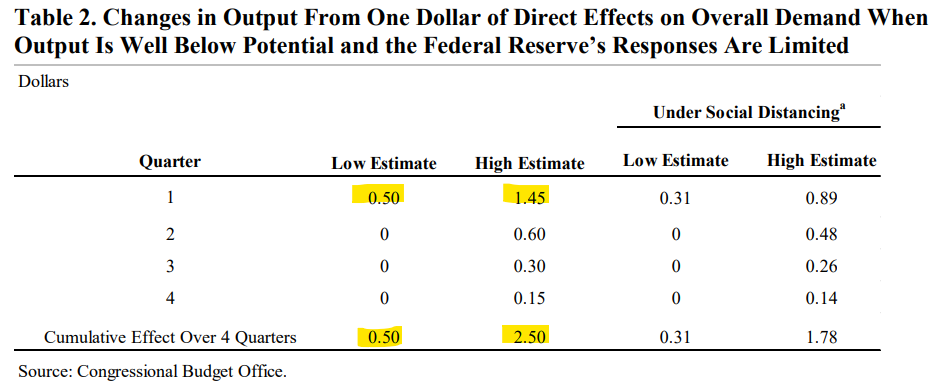

The CBO’s core fiscal multiplier assumptions during the pandemic trace back to a 2020 methodological primer. The paper assumes spending multipliers ranging from 0.5 to 2.5, with a central estimate of 1.5 (see Table 2 below from the paper).

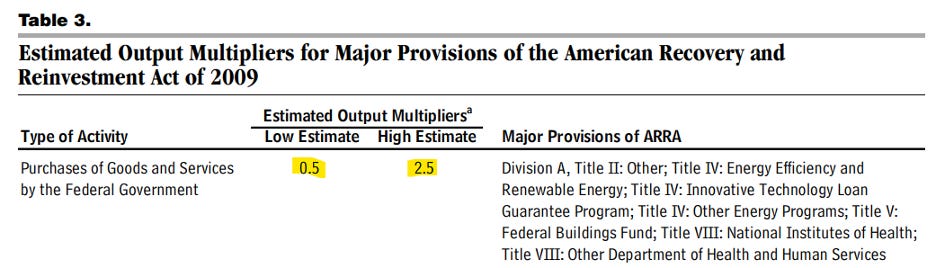

These assumptions are not new. The 2020 primer draws directly from a 2015 CBO paper that estimates output multipliers for major provisions in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009. Table 3 below from this 2015 paper shows the same range of estimates used in the 2020 primer.

Both papers in turn trace their roots to a 2012 CBO working paper, which attempts to estimate short- and medium-term multipliers under various economic conditions. This 2012 paper, for an economy with an output gap, estimates a fiscal multiplier in the range of 0.5–2.5. Without an output gap, the study estimates a range of multipliers from 0.4 to 1.9. In the long run, the paper finds that the multiplier effects turn negative, shrinking the range to 0.4-0.8 after two years. The authors acknowledge that their modeling assumptions are largely based on historical relationships that may not hold during extraordinary circumstances, particularly when fiscal policies deviate substantially from prior norms.

Moreover, the 2012 study relies heavily on earlier studies that apply questionable methods:

Gali et al. (2007) base their results on rule-of-thumb consumers, who are assumed to spend all temporary income — an unrealistic behavior.

Chodorow-Reich’s aggregation of regional data fails to account for spillover effects and weighting issues.

Auerbach and Gorodnichenko use linearized models that often inflate results by ignoring real-world nonlinear dynamics.

These methodological issues are not minor; they severely limit the reliability of the CBO’s central estimates.

Recent Evidence on Temporary Transfers

More recent empirical research confirms that temporary fiscal stimulus typically yields modest output effects:

Dupor et al. (2023) evaluated the local and aggregate impacts of the ARRA and found local consumption response multipliers of just 0.1–0.2 and aggregate multipliers no greater than 0.4. These already muted effects vanish or even turn negative once the central bank begins responding to inflationary pressures.

Ramey (2025) examines four case studies: U.S. tax rebates in 2001 and 2008, and temporary transfers in Singapore and Australia. She finds “little or no stimulus to the macroeconomy” from these policies, with most estimates of multipliers lower than 0.2.

Clemens et al. (2022), focusing on pandemic-related transfers to state and local governments, reach a similar conclusion. Their econometric analysis shows statistically insignificant effects on both income and output, suggesting a multiplier close to zero.

Issues with CBO Assumptions

The inflated estimates stem from several interrelated factors:

Keynesian Bias: The CBO’s models assume a high marginal propensity to consume (MPC), implicitly favoring Keynesian stimulus mechanisms of without sufficiently accounting for neoclassical effects such as crowding out or Ricardian equivalence.

Linear Modeling: Many of the CBO’s source models use linear approximations of macroeconomic behavior, which fail to capture the state-dependent and nonlinear dynamics that dominate real-world fiscal policy effects. As shown by Lindé and Trabandt (2018), this linearization significantly inflates multiplier estimates, especially at the zero lower bound (ZLB).

Neglect of Behavioral Offsets: Rational agents, anticipating future tax liabilities from today’s deficits, may save rather than spend temporary windfalls. This behavioral offset, highlighted in Barro’s Ricardian equivalence framework, is sometimes absent from the studies underlying models used in CBO analysis.

Inflated Emergency Multipliers: The notion that multipliers increase dramatically during recessions or when interest rates are near zero has been tested and found wanting. Ramey and Zubairy (2018), for example, found little evidence that multipliers exceed unity even during deep downturns or at the ZLB.

Implications for Policy

First, it leads policymakers to overspend in the hope of generating short-term stimulus that often fails to materialize.

Second, it contributes to rising debt burdens without a commensurate boost in productive output.

Third, it underestimates the risks of inflationary pressures, particularly when the economy operates near or at full capacity: a hard lesson learned between 2021 and 2023.

Furthermore, large deficits financed by debt issuance can crowd out private investment by raising interest rates and distorting future tax expectations. Several studies have found that in high-debt environments, multipliers not only shrink but can turn negative within a few years (Ilzetzki et al. 2013; Huidrom et al. 2020). These crowding-out effects are amplified in economies like the U.S. one, where capital markets are deep and forward-looking.

The Need for More Realistic Multiplier Assumptions

A more accurate approach to fiscal policy analysis would begin by acknowledging the modest, conditional nature of multipliers. As synthesized from over 150 estimates across 67 empirical studies,

impact multipliers generally fall in the 0.4 to 0.7 range,

peak multipliers are around 0.9, and

long-run effects diminishing over time.

These figures suggest that the CBO's fiscal multiplier of 1.5 or more, especially those used to justify the massive pandemic-era stimulus, is inconsistent with a broad range of empirical evidence. By relying on outdated models, Keynesian assumptions, and simplified behavioral equations, the CBO has propagated an inflated view of fiscal stimulus effectiveness. Rather than assuming a multiplier of 1.5 or larger, the CBO should adopt more conservative estimates grounded in contemporary research. Doing so would promote more prudent budgeting, reduce the risk of debt-driven distortions, and align public expectations with empirical economic realities.

Conclusion: Fiscal Policy Is No Free Lunch

The debate over fiscal multipliers is far from settled, but the weight of the evidence suggests a clear direction: Temper expectations, revisit assumptions, and resist temptation to view stimulus as a panacea. Fiscal policy is not a free lunch, and its returns diminish rapidly when based on faulty premises.