“Deregulated” Energy Markets Still Have a Long Way to Go

Energy markets are complicated. Not only are they steeped in a mountain of rules and regulations, but they also differ among interconnections, states, and municipalities or counties. Despite this complexity, policymakers should understand the basics of energy markets in order to make them as competitive and efficient as possible.

To begin, it is important to understand how energy markets work. In some sense, they are rather familiar. Like other distribution industries, such as grocery stores, they have a wholesale market, where energy is produced, and a retail market, where it is distributed to consumers. More specifically, energy markets have generators, or power plants, that sell energy into the wholesale market. After this, the energy travels over transmission lines, which act as a sort of highway for electricity, and is then received by local distribution centers to be delivered to local households and businesses over smaller cables.

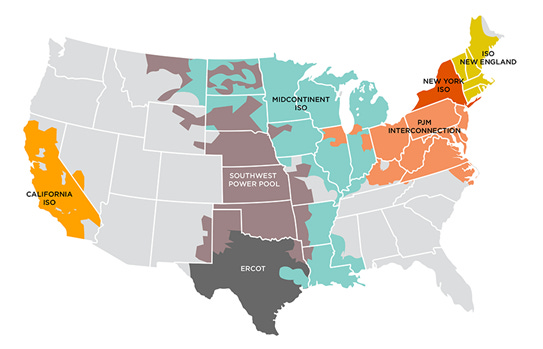

Each of these power plants and sets of transmission or distribution lines exists within something called an interconnection. This is essentially a self-contained region that is separate from other parts of the electric grid. For example, the western interconnection, which covers the western part of the United States, has no intersection with the eastern interconnection, which covers an eastern area of the United States. Thus, there are many parts of the energy distribution system that can be regulated, and many potential regulators at the federal, state, and local levels.

Most people make a distinction between “regulated” and “deregulated” energy markets, though this labeling is rather disingenuous. In a regulated energy market, one entity controls the entirety of the energy production process. These entities act as traditional vertically integrated monopolies, in the sense that they produce the power and transmit it to local sites, where it can then be distributed to firms and households. These monopolies are typically publicly owned utilities, owned and operated by the government. The prices are set by the government, which also makes and enforces all innovations, policies, and developments.

All these systems are backed by a mountain of regulations regarding energy generation practices, pricing models, transmission channels, and more. The purpose of these regulations seems to be to provide stability and reliability, under the general premise that this system is as good as it needs to be and that any deviations from it would harm the common good.

The trouble is that, in most conceptions of free-market economics, maintaining a rigid, unchanging system isn’t a good thing. The economy is a dynamic system, whereas the government is nothing if not static. Thus, it should come as no surprise that as energy markets have evolved, so too have their regulations to better induce competition, fairness, and stability.

The efforts to deregulate started, rather counterintuitively, with further regulation when the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, or FERC, was established. Following the creation of the Department of Energy in 1977, FERC was born and given the power to issue orders under the Federal Power Act, which is the statute that directs energy market regulation. The Energy Policy Act of 1992, coupled with a series of orders from FERC, gave rise to our modern conception of the “deregulated” energy market.

Deregulated markets dissolved the vertically integrated monopoly, introduced retail competition, or “customer choice” regarding who generates the energy, and created the Regional Transmission Organization (RTO). What these changes mean in practice is different for each RTO. For example, CAISO, the RTO in California (see Figure 1), operates the grid, while the transmission lines are owned by investor-owned utilities. Generally speaking, RTOs manage, or regulate, the use of transmission lines, essentially kicking the regulatory can down the road, away from the more competitive generators.

Another role of FERC, however, is to maintain stable prices in the wholesale market for electricity (that is, the price that utilities face when purchasing from generators). More locally, states regulate retail prices, establishing another layer of control over the market. Thus, it should come as no surprise that prices in “deregulated” markets are generally equal to or higher than “regulated” market prices.

The word “deregulated,” then, is clearly not a sufficient differentiator between these two markets. A better, and similarly common, term is “restructured.” This term avoids the confusion that comes with saying the market is deregulated when it is also closely watched and controlled by the government.

Thus, even though restructured markets have incorporated free-market principles, they still have a long way to go before they achieve more recognizable gains in efficiency, pricing, and innovation. Current regulations on pricing, transmission and distribution of energy, and more, have all but voided the workings of markets, price signals, and the long-run competition that drives market behavior.