Developing Countries Won’t Get Rich Without Institutional Reform

Last week, Professor Nelson Camilo Sánchez of UVA’s School of Law wrote an article in which he called for a crackdown on international corporate taxation with hopes that this would transfer a greater degree of wealth and prosperity to developing nations. And while Sánchez’s sentiment is nice, being that poorer countries should have access to greater support and development, his solution isn’t supported by economic evidence. In fact, likely, he is inadvertently calling for an increase in inequality and slower economic growth globally.

Sánchez begins his analysis by citing the Tax Justice Network, which claims that $480 billion of taxes are lost to tax “abuse” each year, globally. This is a weak claim for a few reasons, one of which is the mentioned figure, and another is the use of the word “abuse” in this context. Disproving this point is beyond the scope of my response, but take, for a moment, that this statistic is true. What are the consequences of his resulting claims?

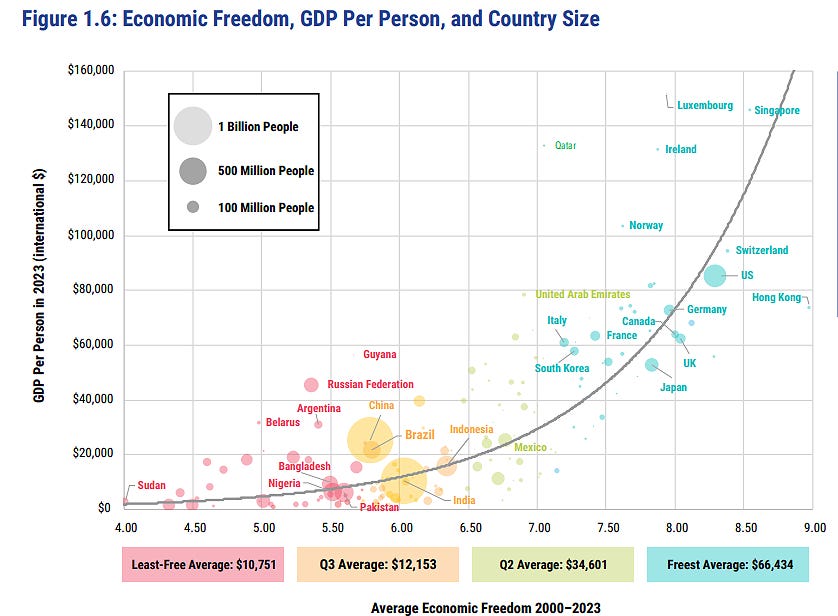

The core of Sánchez’s argument is that certain countries lack human rights, and this is directly related to a lack of resources. A common narrative, when speaking about how we can help developing countries, is to give aid in the form of money. This is a natural solution for most, seeing as the lack of money appears to be the issue. However, it misses the point, being that institutions are unstable, and, in reality, reinforces the issues at hand rather than addressing them. Furthermore, it fails to address the problem of economic freedom being one of, if not the most, important factor when determining a nation’s ability to grow, and that a great many poor nations lack the proper freedoms to properly utilize the aid received.

Much of Africa acts as a perfect example, annually receiving somewhere between $60 and 80 billion in aid while also seeing little to no significant year-over-year increase in real GDP per capita. This is largely because of institutional degradation, corruption, and the perversion of incentive structures that come about naturally in the absence of interference. These systems highlight low economic freedom, and place much of Africa as far less economically free than much of the rest of the world. With these current systems in place, when money is sent to much of Africa, it ends up in the pockets of corrupt politicians and charity workers who exploit the lack of a stable system that ensures the funds benefit the impoverished. Thus, no amount of excess funds can fix this broken system, and in fact, these funds seem to instead be ensuring that the system remains in place rather than the other way around.

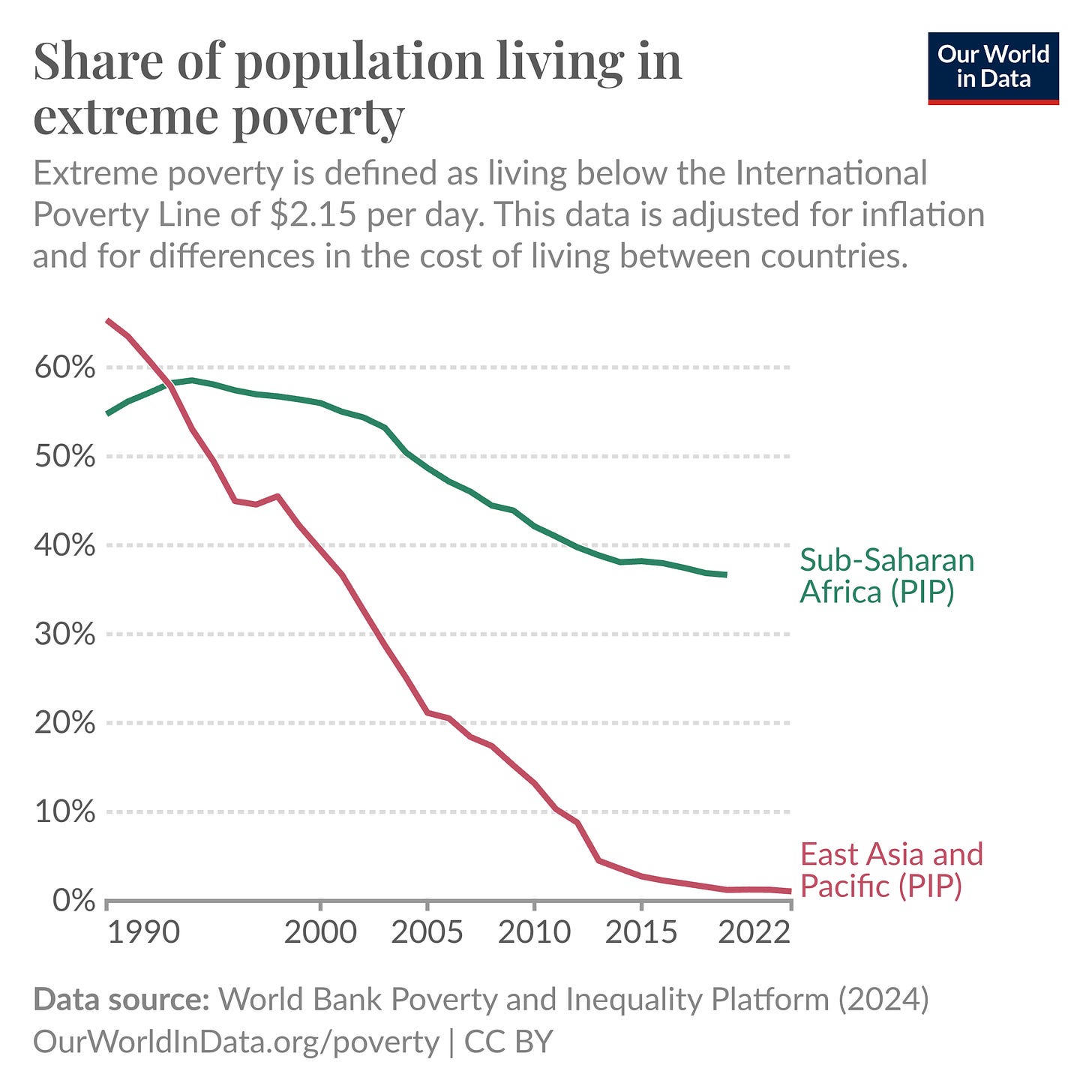

Often, when this is mentioned, people who support sending foreign aid to developing nations refer to the fact that this might not be a perfect system, but suspect that it is doing at least a little bit of good. In actuality, it appears that this form of foreign aid is not only not working, but could instead be actively harmful. In 1990, 55% of Sub-Saharan Africa was in extreme poverty, whereas in East Asia and the Pacific, 65% was. Today, less than 1% of East Asia and the Pacific is in extreme poverty, while 37% of Sub-Saharan Africa is. For context, while the amount of aid nearly tripled in Sub-Saharan Africa during this time, it remained relatively static in East Asia and the Pacific, at around $10 billion.

Why might this be? Foreign aid can act like a government subsidy and distort the incentives to grow an economy. So, beyond the existence of corruption and a mismanagement of funds, there is also little incentive, when foreign aid is present, to create domestic infrastructure. If a charity in the United States sends shoes to an African country, while it is true that in the best-case, shoes are being provided, it is also true that local cobblers have less business and less incentive and ability to grow their businesses. This is not an argument against global trade, but rather suggesting that foreign aid crowds out private, domestic industry when it is especially important for long-term growth.

But even if an increase in resources were a proper solution, Sánchez’s proposed method is rather dubious. On paper, taxing corporations further sounds nice to some, especially when approached with the moral position that taxing the rich to benefit the poor is a good thing. However, in reality, corporate taxes are not so clean and obvious and end up being much more harmful than they might initially seem.

On one hand, the incidence of corporate tax increases falls largely on workers and consumers. This means that when a firm sees an increase in a tax rate, it will typically compensate for this through an increase in prices faced by consumers and decreases in wages given to workers. On the other hand, corporations are largely responsible for innovation, research and development, and the growth in the investment arm of the economy, meaning that taxing them more heavily creates a drag on output. In fact, of all tax policies, it is estimated that an increase in corporate tax rates has the largest drag. Economic development and welfare, as mentioned above, are essential to the flourishing of a society, making this quite an unattractive policy.

When critiquing the arguments that I have presented, one might note how quickly I turned to the point of foreign aid, and respond by saying that this isn’t a conversation about foreign aid, but rather about reasonable and transparent taxation. This, however, doesn’t undermine my main point, which is that poverty does not, in fact, come from a lack of resources, as described by Sánchez, but rather from a lack of stable institutions and low economic freedom. I don’t disagree that resources allow for growth, and I am not arguing that these countries should never engage in domestic tax reform, but I dispute that having this enforced by the UN is a good idea, and I dispute that the proposed solution would, in fact, distribute resources in the way he believes. In essence, by insisting on reformed tax practices on a macro scale but not on reforming the distributive policies of these funds, they are no better than the distorted foreign funds that are contributing to the present issues.

Now, both ends of the proposed policy solution lack credibility, and the situation only worsens when one puts them together. In essence, these policies would be taking money from poorer laborers throughout the global economy, the people who need the money most, and transferring it to corrupt, rich politicians in developing countries. So, while this solution appears to be an avenue towards a decrease in inequality and further global economic growth, it is likely that it would have the exact opposite effect, promoting instead corrupt institutions, a slower economy, and a failed system that relies too heavily on foreign aid.

Brilliant breakdown of why throwing money at development problems usually backfires. The East Asia comparison really drives it home since both regions started at similar poverty levels in 1990 but diverged massively based on institutional quality rather than aid volumes. I've seena few SMEs try to expand into African markets and the biggest roadblock was never capital but navigating unpredictable regualtory environments where contracts mean little. The incentive distortion angle is underrated too, when aid crowds out local entrepreneurs it undermines the exact engine thats needed for sustained growth.

I wholeheartedly agree with the thrust of your piece.

But as your second chart demonstrates so well, any focus on foreign aid misses the forest for the trees.

East Asian property rates have plummeted in the last 35 years while Sub-Sharan African ones have not primarily because the former have to a great degree adopted free-market economic policies while the latter have not.