How Much Did Macroeconomic Policy Matter?

A New Decomposition Reveals the Dominant Role of Demand in the 2021–22 Inflation Surge

The inflation surge of 2021–22 remains one of the most significant macroeconomic events in recent history, not just because of the sharp price increases, but because of what it revealed (and continues to reveal) about the role of policy in shaping economic outcomes. For years now, we’ve witnessed a pitched battle between two competing narratives. One narrative blames the inflation spike on a string of unfortunate supply-side shocks: pandemics, wars, and disrupted supply chains. The other sees the culprit squarely in the realm of macroeconomic policymaking: stimulus spending, accommodative monetary policy, and political miscalculation.

A new working paper by my colleagues David Beckworth and Patrick Horan (now at Fiscal Lab on Capitol Hill) adds crucial support to the latter narrative. Their study, titled “How Much Did Macroeconomic Policy Matter? A New Decomposition of the US Inflation Surge of 2021–22,” provides a sophisticated empirical analysis of the inflation surge. Using both a refined nominal GDP-based framework and a structural vector autoregression (SVAR) grounded in New Keynesian theory, they show that the inflation of 2021–22 was not the result of an unpredictable storm of exogenous shocks, but rather the predictable consequence of excessive aggregate demand, fueled by unprecedented policy stimulus.

The Supply Shock Trinity vs. the Demand Overshoot

Beckworth and Horan begin by acknowledging the prevailing “trinity” hypothesis — the idea that inflation was driven by a three-headed supply-side monster: (1) a COVID-induced shock to consumer preferences (especially toward durable goods), (2) commodity disruptions from the Russia–Ukraine war, and (3) tight labor markets caused by pandemic-related constraints. This perspective, popularized by economists such as Ben Bernanke and Olivier Blanchard, portrays inflation as a kind of perfect storm: unfortunate, exogenous, and largely beyond the reach of policymakers.

Beckworth and Horan, however, offer a different perspective. They argue that while supply shocks shaped the distribution of inflation across economic sectors (e.g., durables versus services), they cannot explain the magnitude of inflation. To generate a sustained, broad-based rise in the price level, rather than just relative price shifts, there must be excess nominal demand. And that, they say, was largely the result of deliberate policy choices.

Method One: The Furman Decomposition (Revisited)

Beckworth and Horan’s first empirical approach builds on the now-influential “Furman decomposition,” named after Jason Furman, which splits deviations in nominal GDP (NGDP) into price-level effects and output effects. If NGDP rises above trend, that extra spending must show up in either more real output or higher prices. The question is: which one?

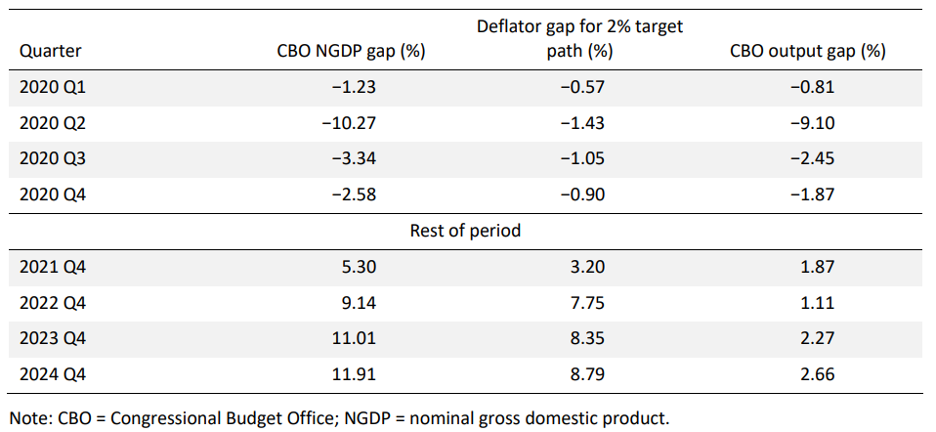

Beckworth and Horan replicate Furman’s decomposition but enhance it with improved data. They use ex-post estimates of potential real GDP from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO, January 2025), eliminating concerns about real-time forecast errors. Their findings are striking:

By the end of 2022, NGDP had overshot its pre-pandemic trend by 9.14%, of which 7.75% absorbed by the price level and just 1.11% contributing to real output.

By the end of 2024, the gap had widened further, with 8.79% of excess nominal spending absorbed as inflation.

TABLE 1. Furman decomposition from Beckworth and Horan's paper (Table 2)

In other words, the surge in NGDP was mostly “soaked up” by prices, not output, confirming that the economy’s productive capacity was relatively inelastic and that pushing demand beyond capacity simply created inflation.

Method Two: A Structural VAR Decomposition

To bolster their case, the authors turn to a structural New Keynesian model and implement a vector autoregression (VAR) with long-run identifying restrictions. This approach allows them to distinguish between three types of macroeconomic shocks:

Aggregate demand shocks (e.g., stimulus, monetary policy)

Temporary supply shocks (e.g., port congestion, chip shortages)

Permanent supply shocks (e.g., productivity changes)

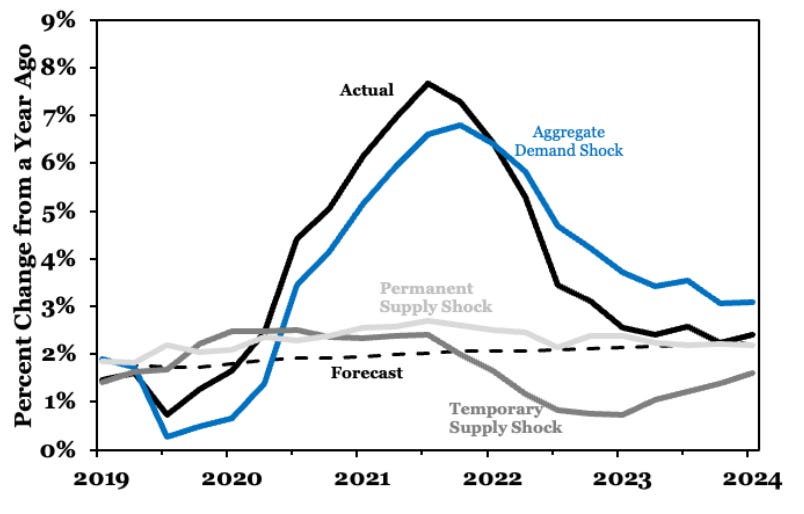

Using impulse response functions and historical decompositions, they find the following:

Aggregate demand shocks accounted for more than 60% of excess inflation in 2021 and more than 85% in 2022.

Temporary and permanent supply shocks played a comparatively minor role.

In total, aggregate demand shocks pushed the GDP deflator roughly 9% above forecast by the end of 2024, mirroring the results from the simpler NGDP approach.

FIGURE 1. GDP deflator inflation from Beckworth and Horan's paper (Figure 4)

A Credible Disinflation, Not a Lucky One

Another important insight from Beckworth and Horan’s analysis is that disinflation was driven by waning demand, not by an economic crash or improved supply. Inflation fell from 7.1% in 2022 to 2.4% in 2024 without a recession — evidence, the authors argue, of a credible monetary policy response. The Fed tightened, inflation expectations adjusted, and nominal demand returned to a more stable path.

This is important. It suggests that disinflation didn’t require mass unemployment or a “Volcker shock.” What it required was credibility and patience — two things that are often in short supply.

Why This Paper Matters

This paper doesn't just revisit the causes of recent inflation; it offers a blueprint for future macroeconomic analysis. Its central message is clear: If you want to understand inflation, watch nominal demand.

Massive fiscal injections like the American Rescue Plan Act, particularly when layered atop preexisting demand support, will translate into inflation when the output gap is small or already closed.

Monetary policy must pay attention not only to interest rates or unemployment, but also to nominal GDP and its deviation from trend. Supply shocks explain relative price changes, but only demand shocks explain generalized, persistent inflation.

In short, inflation is not mysterious. It doesn’t require novel theories like “greedflation” or hidden corporate conspiracies. It’s the result of too much money chasing too few goods, especially when that imbalance is driven by policy.

Final Thoughts

Beckworth and Horan’s decomposition should be the final nail in the coffin of the “it was all supply-side” narrative. The inflation surge of 2021–22 wasn’t a random act of economic nature — it was the direct result of macroeconomic excess, plain and simple.

And that matters — not just for how we assign blame, but for how we prepare for the future. If policymakers don’t learn the right lesson — that overheating an economy already at capacity will yield inflation, not growth — then they risk repeating the same mistake under a different name.

As the authors themselves put it: “The broad-based rise in the price level was primarily the result of excess aggregate demand … Supply shocks alone would likely have resulted in sectoral reallocations … rather than a sustained increase in overall inflation.”

The evidence is in. The verdict is clear. Macroeconomic policy mattered — a lot.