“Laffer Curves Are Flat”

The Revenue-Maximizing Tax Rate and Fiscal Consolidation

A new paper by Rachel Moore, Brandon Pecoraro and David Splinter—bluntly titled “Laffer Curves Are Flat,” in reference to the model of a curve illustrating an optimal tax rate to maximize revenue—ought to change how people talk about “taxing the rich” and the fabled 73% top tax rate often invoked in policy debates. The paper finds that when you model taxes the way they actually work in the U.S., and when you allow the economy to respond fully, the long-run Laffer curve around the top tax rate is surprisingly flat.

That means big changes in the statutory top tax rate produce almost imperceptible changes in total government revenue. For anyone tempted to tout a 70-plus-percent optimal top rate as a revenue lever, this paper is a corrective. For those worried about fiscal consolidation, reducing budget deficits through higher taxes and/or less spending, it’s a warning: Tax hikes at the top are a poor substitute for genuine spending restraint.

What the authors do differently

Most prior work on revenue-maximizing top rates falls into two camps. “Sufficient-statistic” calculations (the sort that underlie Piketty, Saez and Stantcheva’s oft-cited 73% figure) collapse the tax system into a single formula and feed it two inputs: an inequality parameter and an elasticity of taxable income (ETI). The issue with this approach is that it hinges almost entirely on one behavioral number (the ETI). Making small changes to that number or adding omitted behaviors like migration, avoidance, innovation or human-capital responses radically changes the optimal rate estimate.

Mirrlees-style macro models, by contrast, build full general-equilibrium frameworks but then usually simplify the tax code into smooth, one-base functions. The issue with this approach is that it collapses the tax code into a smooth, stylized function that bears little resemblance to the actual tax system. That means these models understate how much tax design, not just taxpayer behavior, matters for revenue outcomes.

This new paper by Moore, Pecoraro and Splinter combines the best of both approaches: a heterogeneous-agent, overlapping-generations macro model with a realistic tax calculator that reproduces the quirks of U.S. law (ordinary vs. preferential income, surtaxes, alternative minimum tax, passthrough deductions, filing status, etc.), calibrated to administrative data covering very high incomes.

Why the methodology matters

Two mistakes common in earlier work drive exaggerated revenue estimates: (1) treating all income as if it faces the same marginal tax rate (a “broad base” that misclassifies preferential capital gains as ordinary income), and (2) treating only wage income as the top-rate base (a “narrow base” that ignores substantial ordinary capital and passthrough income). Both simplifications miss the real margins high earners use to avoid taxation, such as shifting income between ordinary and preferential tax bases, reallocating activity between noncorporate (passthrough) and corporate sectors, and altering tax-preferred consumption and investment decisions.

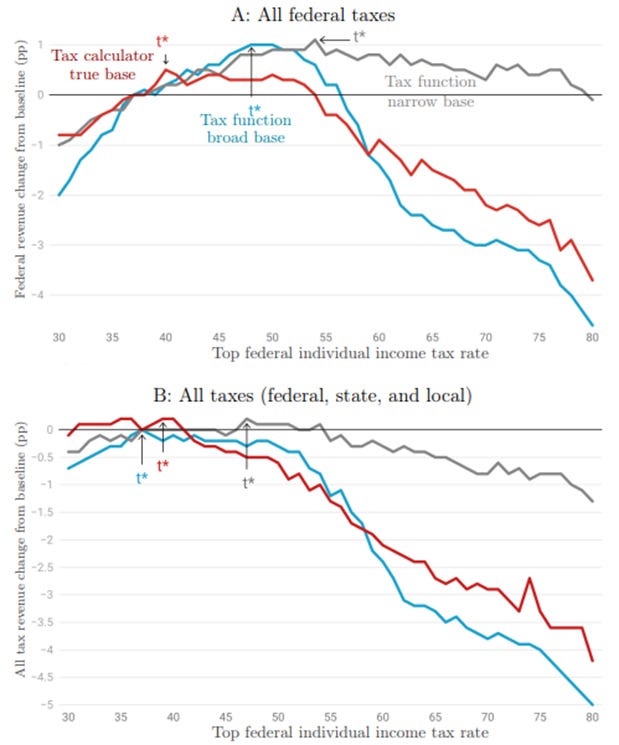

Once those margins and full firm responses are included, the Laffer curve flattens—that is, increasing or decreasing the top tax rate doesn’t have much effect on revenue. Relative to naïve specifications, the realistic calculator lowers the revenue-maximizing top rate and shrinks the potential revenue gains. Put concretely: Under these authors’ “true base” tax calculator, the revenue-maximizing top rate sits far below the oft-quoted 73%, and the additional federal income tax revenue from raising the top rate by two percentage points (to 39%) amounts to only about 0.2%, or less than 0.1% of GDP.

What this means for the often-claimed 73% optimal top rate

Piketty, Saez and Stantcheva’s 73% figure follows directly from the sufficient-statistic algebra if you assume a Pareto parameter of 1.5 and a total ETI of 0.25—that is, you assume very high incomes will “thin out” at a certain rate and rich people won’t change their behavior when tax rates change. The new study shows exactly why that calculation is fragile, however. The sufficient-statistic result is extremely sensitive to the ETI and to what you count as taxable “top income.”

If you allow realistic cross-base shifting and the full macroeconomic feedbacks that follow, the effective ETI is larger than the 0.25 used in many headline calculations; using empirically plausible higher ETIs collapses the 73% result into much lower revenue-maximizing rates (and in some extensions, into the conclusion that raising top rates actually loses revenue when all taxes and mobility effects are accounted for).

In short, the 73% number is an artifact of a tight set of assumptions, narrow treatment of tax bases, optimistic assumptions about behavioral inertias, and ignoring sectoral and tax-interaction channels. When you model the tax code the way Congress actually writes it and the economy the way firms and households actually respond, the fantasy of large revenue gains from punitive top rates evaporates.

Implications for fiscal consolidation

That brings us to the politically urgent question: If raising top rates can’t meaningfully close budget gaps, what can? Moore, Pecoraro and Splinter give a blunt policy lesson: There is very little fiscal space left at the top. Their estimates imply that pushing the top statutory rate to revenue-maximizing levels produces only trivially small increases in total government revenue, on the order of a few tenths of a percent of GDP once you account for all federal, state and local taxes. Even a sizable statutory hike produces only modest aggregate revenue changes because the system’s complexity and the economy’s responses blunt the revenue payoff.

That reality should reframe debates about consolidation. If the goal is materially lower deficits or slower debt accumulation, reliance on additional top-rate increases is futile. Unless policymakers are prepared to extract far larger and more distortionary tax bases, substantive fiscal improvement will have to come from spending reductions or reforms that measurably shrink entitlements, subsidies and recurring outlays. In plain terms, after you squeeze the low-hanging fruit on revenue (and the paper suggests that fruit is small), the only lever left with the magnitude needed is spending.

The equity-efficiency tradeoff

The authors also emphasize that on the flat portion of the Laffer curve, the normative choice is not about revenue so much as it is about distribution versus growth. If raising the top rate generates little revenue but does increase progressivity, the question becomes whether that modest redistribution is worth the growth penalty. That is a legitimate political judgment. But it is a different debate than the one framed by the 73% “optimal” rhetoric, which treats punitive top rates as a revenue engine rather than a distributional instrument with real efficiency costs.

In sum, this new paper forces a clearer accounting of behavioral margins, tax bases and macro interactions. For advocates who imagine that simply “raising the top rate” will deliver a fiscal elixir, the paper offers a sober correction. And for policymakers serious about fiscal consolidation, the paper is a reminder that the heavy lifting will have to be done on spending, not by squeezing a barely profitable top rate.

What about different tax regimes? If we taxed things more efficiently (e.g. more property/land taxes and less income/wealth taxes), the Laffer curve should be less flat. And then we could 'raise' them higher and get higher revenues from higher taxation. Any suggestions for how much this would matter?