Millionaire Taxes Don’t Deliver: Lessons from New York and Massachusetts

New York and Massachusetts Show the Limits of Progressive Taxation

Zohran Mamdani, the socialist New York State Assemblyman now running for mayor of New York City, has a simple plan to fund his ambitious and expensive policy platform: tax the rich. It’s a populist message, one that seems politically convenient in a city home to many of the country’s wealthiest residents. But history, tax data, and empirical economics suggest this idea is not only flawed but likely counterproductive.

New York’s Millionaire Tax Experiment

In 2021, then-New York governor Andrew Cuomo, now considered Mamdani’s main rival, raised the state’s top marginal tax rate on earners making over $1 million. He also introduced two new brackets for those earning over $5 million and $25 million, with a top rate of 10.9%. In New York City, taxpayers will also have to pay the 3.9% city income tax, for a top combined state and city rate of 14.8%.

The goal of this tax reform was to increase revenue and finance more generous public programs.

So, what happened?

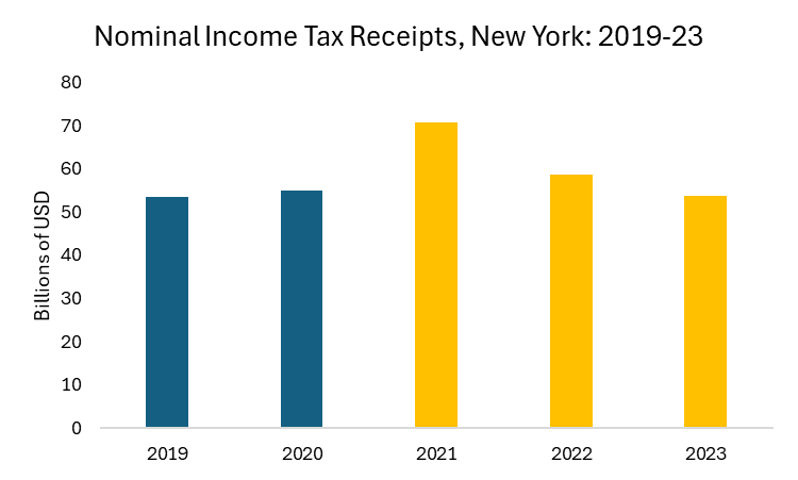

As Figure 1 shows, in nominal terms, income tax revenues rose briefly in 2021, then quickly returned to pre-2021 levels in 2022 and 2023. The blue bars show income tax receipts before the 2021 reform, while the yellow bars show income tax receipts after the millionaire taxes were enacted.

Figure 1.

This spike in 2021 reflects a combination of temporary post-COVID windfalls and anticipatory income shifting as wealthy taxpayers realized more income that year ahead of higher rates kicking in fully. But by 2023, receipts had fallen back to pre-hike levels.

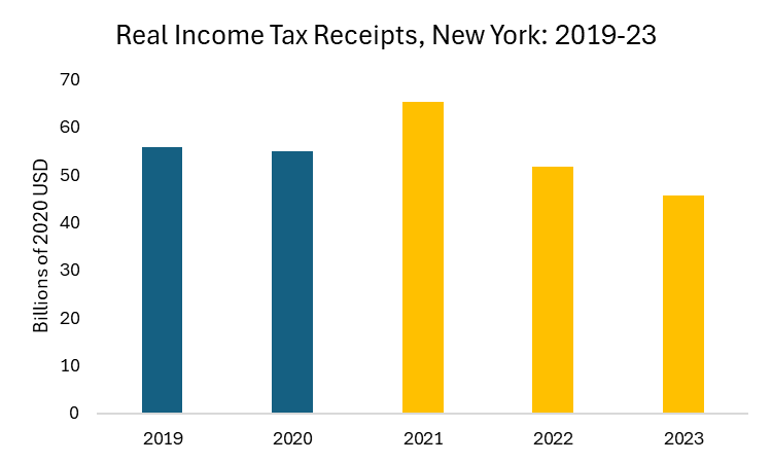

Adjusted for inflation (2020 dollars), the picture is even worse. Figure 2 shows that, yes, revenues did spike in 2021 in real terms, but by 2022 and 2023 they had declined significantly, dropping to about $46 billion in 2023 in real terms versus $55 billion in 2020.

Figure 2.

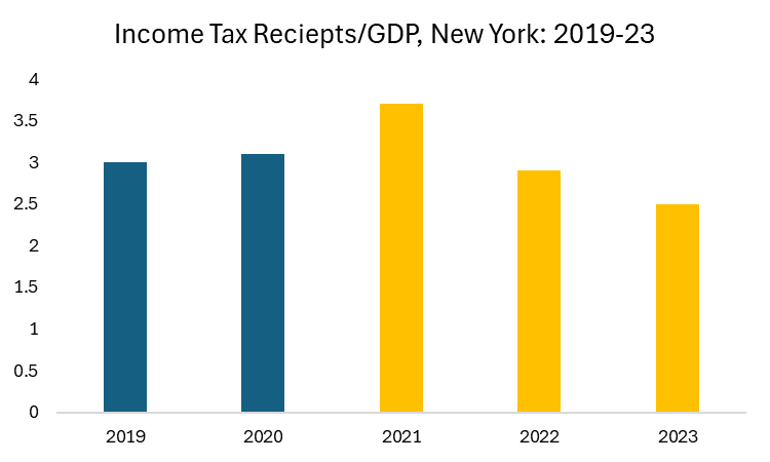

One final way to measure changes in income tax receipts is to look at these revenue figures as a share of state GDP. Figure 3 shows income tax receipts in New York as a share of the state’s gross domestic product.

Figure 3.

Despite higher tax rates, New York state now collects less income tax revenue relative to the size of its economy than it did before the hike. High earners didn’t just sit still and hand over a larger share of their income. Many left, rearranged their finances, or deferred income.

According to IRS state migration data, from 2021 to 2022, New York state lost, on net, over 60,000 residents who moved to Florida and took with them their combined $6 billion in adjusted gross income. Of the more than $36 billion that left the state in 2022 (a net loss of $14 billion), nearly 60 percent came from individuals earning more than $200,000.

Massachusetts Tried Too

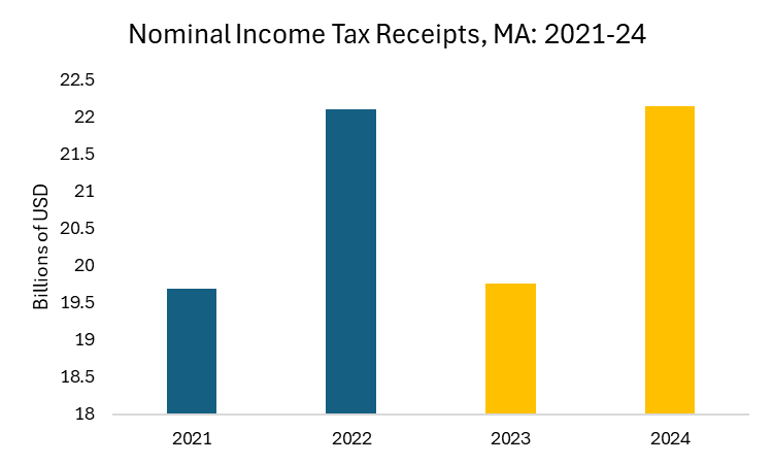

New York isn’t the only state to impose additional taxes on millionaires in recent years. In 2023 Massachusetts imposed a new 4 % surtax on incomes over $1 million added to its existing 5% flat tax. Voters approved this measure via referendum in 2022, and politicians promised a surge of new revenues.

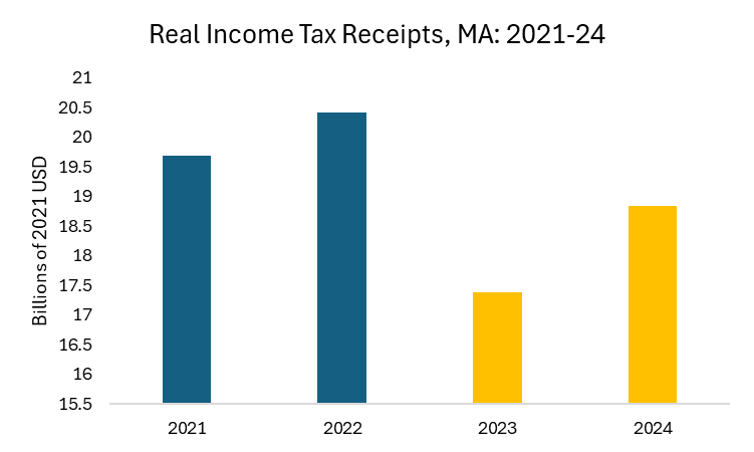

However, nominal income tax revenue (billions) actually declined in the first year the surtax was collected, before rebounding the following year. Figure 4 shows the changes in income tax receipts in Massachusetts from 2021 to 2024.

Figure 4.

The revenue data looks notably worse when you adjust for inflation (Figure 5):

Figure 5.

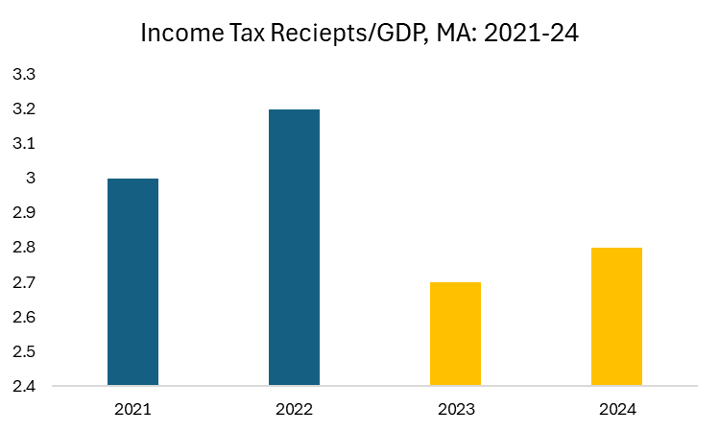

And worse again, as a share of state GDP (Figure 6):

Figure 6.

Massachusetts, like New York, is seeing the limits of trying to squeeze more from its highest earners. The surtax hasn't raised new revenues for state government. In fact, it has led to notably lower levels of income tax receipts.

High-income earners can defer, reclassify, shift, or relocate their income. New York and Massachusetts have learned this the hard way.

The Mirage of Millionaire Taxes

The evidence is clear: Soaking the rich may win applause on the campaign trail, but it doesn't pay the bills. In both New York and Massachusetts, steep new taxes on high earners have failed to generate sustainable revenues. In real terms and as a share of GDP, income tax receipts have declined since these policies took effect.

This is not a fluke — it’s the predictable outcome of taxing a highly mobile and responsive tax base. Economists have long documented that top earners respond strongly to changes in marginal rates. They shift income, change residency, delay realization, or simply leave.

If Zohran Mamdani wins the mayoralty and attempts to finance his broad slate of expensive programs by taxing the rich, he will quickly discover the same fiscal limits already visible in New York and Massachusetts. The expected revenue won’t materialize, but the economic costs will. Lavish spending plans built on the myth of bottomless millionaire tax revenues are destined to collapse under their own weight.

Policymakers who ignore this reality risk hollowing out their tax base while undermining long-term growth. A tax system that depends on punishing success and capital will ultimately discourage both. Instead of chasing populist illusions, New York City needs tax policy grounded in economics — not ideology.