No, the OBBBA Won't Pay For Itself

Larry Kudlow's projections about the OBBBA are faulty

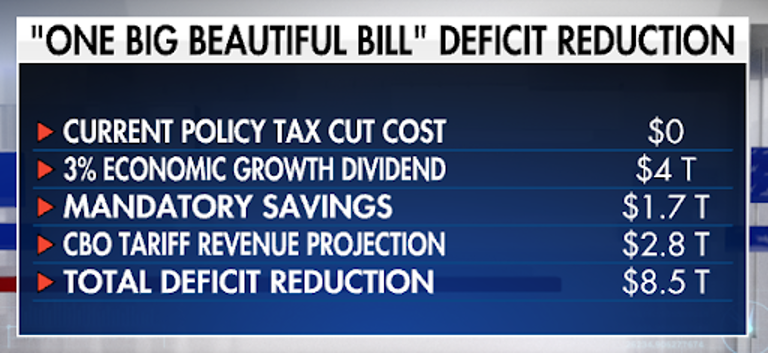

Larry Kudlow claims that the One Big Beautiful Bill (OBBBA) will pay for itself. He offers this calculation:

According to him, the OBBBA will reduce the deficit by $8.5 trillion. These are different projections from those given by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and other groups. For instance, the CBO says the bill will cost $2.4 trillion over ten years. The Committee for Responsible Budget has this number closer to $3 trillion. The Tax Foundation predicts the cost will be $2.6 trillion ($1.7 trillion with dynamic scoring)

Kudlow’s projections are widely off base. That would be fine, except that in recent weeks, I have been hearing a few people repeat these claims.

It’s not that I don’t believe that tax cuts can be very pro-growth or can pay for themselves. As the Cato Institute’s Adam Michel points out, pro-growth tax cuts – the kind that broaden the tax base, close loopholes, and remove incentives to invest, save, and work – can eventually offset their initial revenue losses by expanding the economy by so much that tax revenues rise. It’s not a question of if revenues will surpass the original baseline, but when. Tax cuts always produce revenues below the baseline at the beginning, but if the growth is strong enough this trend will reverse over time.

With that in mind, let’s look at each line in Kudlow’s projections.

Current policy tax cut cost: $0

The first claim made is that we shouldn’t trust the CBO because it makes a lot of mistakes, including wrongfully projecting the cost of the TCJA in 2017. Kudlow said "The current cost of the 2017 tax cuts should be zero. Why should they be zero? Because they produced more revenues, $2.3 trillion more revenues than CBO estimated over the past seven years." This is a talking point we hear repeatedly among Republicans these days.

Revenue forecasting is inherently difficult. It is true that the CBO didn’t accurately project the rise in revenue over the ten years after the adoption of the TCJA. However, contrary to this claim, it is not because the tax cuts’ impact on revenue was off base, but because these projections were overwhelmed by new legislation and unforeseen economic events.

Here are some of the reasons their revenue forecast was not accurate: high inflation, the growing trade war, the pandemic, a war in Europe, a new conflict in the Middle East, numerous tax changes in response to the pandemic, natural disasters, the CHIPS Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act, and higher-than-expected immigration. When you adjust for the unforeseen inflation that boosted revenue, you can see that the CBO wasn’t that far off.

In other words, it is inaccurate to claim that the additional revenue over the period was the product of the TCJA. This isn’t to say that the TCJA wouldn’t have eventually pay for itself either. It would have in large part because it was a good tax reform with many pro-growth elements to it.

Even if we grant that the CBO had been way off in its TCJA projections, this fact alone tells us nothing about what the cost of the OBBBA will be. First, the new legislation is made of more than the extension of the TCJA’s expiring provisions. According to my colleague Josh Rowley, the OBBB adds about $1.3 trillion in additional tax cuts that go beyond TCJA extension. That equals to 34% of the bill’s total revenue loss. In other words, there are more costs to this bill than those that come from simply extending TCJA.

We also shouldn’t expect the same boost from maintaining lower tax rates as we got from actually lowering tax rates. I assume that Kudlow believes that the unexpected revenue from TCJA is the product of growth that CBO didn’t foresee, but there is no reason to believe that extending provisions that are already in place, and that most people expected would be extended, will boost the economy as much cutting taxes as the TCJA did eight years ago.

That leads me to a beef I have with people like Kudlow – but also many in the Senate – who believe that we should use the current policy baseline (baseline as if the TCJA cuts were always going to be extended as opposed to expiring) to measure the cost of the extension ($0). People like this want to have it both ways. They claim that the fiscal cost of extending the 2017 tax cuts should be measured against today’s tax code, rather than against the code to which we would revert if the cuts automatically expired. They argue that assuming the cuts will be extended reflects the common expectation among taxpayers and markets.

But if markets already expect extensions, then making the tax cuts permanent cannot generate significant additional economic growth. The growth that these tax cuts can achieve has largely been realized. Merely continuing with lower rates doesn't unleash many new incentives or productivity.

3% Economic growth dividend: $4 trillion

I have heard Kudlow make this point many times on his show. “Now, I believe there will be a growth dividend which may be debatable, but if I plug in 3% growth instead of the CBO's lowball 1.8%, then I actually get $4 trillion worth of additional revenues for purposes of deficit reduction."

Why he believes his 3% is more plausible than the CBO’s estimate, he doesn’t say. Part of this is that he believes that CBO is often wrong. Also, he likely believes that all tax cuts are massive growth-generating machines. But that’s not the case. While the OBBBA will avoid a significant tax increase as it introduces a few excellent provisions, such as eliminating some of the Inflation Reduction Act subsidies, the bill is structurally flawed. As mentioned, the bill extends the TCJA expiring provisions, but it also includes costly, low-growth (or anti-growth) provisions such as:

Raising the SALT deduction cap, benefiting high-income taxpayers. The Tax Foundation estimates that this provision reduces growth by 0.5%

It creates or extends approximately 20 tax expenditures, which makes the tax code less efficient and more complicated. These tax breaks, such as exempting tips from taxation, barely produce any growth. This is what a principled approach to tax expenditures would look like.

The most pro-growth policies like the 100% Bonus Depreciation, R&D expensing, and Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization (EBITDA are extended only for 4 years.

It requires more borrowing. Interest on the debt resulting from the additional deficit will offset the spending reduction.

While Kudlow can truthfully say that if we get 3 percent economic growth, we would get a $4 trillion increase in revenue, the flaws in this bill make any such growth rate very unlikely. Credible estimates from across the political spectrum show the minimal effects of OBBBA on growth:

Economic Policy Innovation Center: 0.5%

Tax Foundation: 0.8%

Yale Budget Lab: 0% (only 0.2% temporarily between 2025-2027)

Penn Wharton Budget Model: 0.4%

It gets worse because most economic models don't adequately consider the negative consequences on long-term growth of ballooning federal debt. High levels of debt put upward pressure on interest rates, crowding out private investment and dampening long-term growth prospects. Historically, higher debt lowers economic growth.

Finally, many of the defenders of the bill like to point to other aspects of the Trump agenda that have the potential to be extremely pro-growth, like energy abundance and AI dominance, to justify claims of high growth doing the next few years. However, this pro-growth potential doesn’t say anything about the growth potential of the OBBBA.

Mandatory Savings: $1.7 trillion

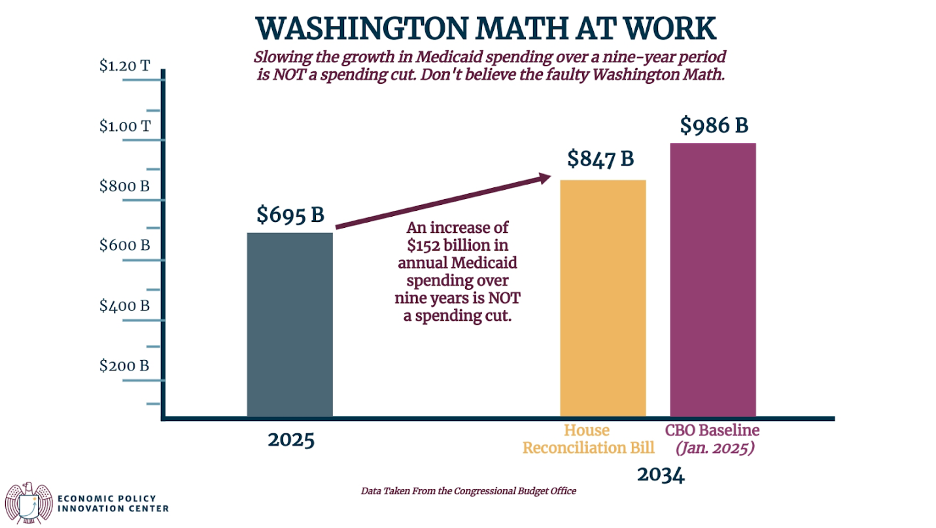

The House should be applauded for including some spending cuts. But let’s be honest: these cuts are mostly reductions in the growth of spending rather than actual cuts. Take Medicaid. Our friends at EPIC put this chart together:

In light of the spectacular growth in Medicaid spending since 2019 (see this chart on p. 6 of the chartbook of Inflation-Adjusted Medicaid Welfare Spending), it is less of an accomplishment than it seems. Moreover, if Congress wants to give the American people more tax cuts than it gave in 2017, then it should cut spending because you can’t have it both ways. In other words, they should have cut way more. In fact, as Jack Salmon has pointed out, the OBBBA offers a partial fix to the medical provider tax loophole, but they should eliminate this altogether. CBO estimates that would save more than $600bn over 10 years.

CBO Tariff Revenue Projection: $2.8 trillion

While Kudlow believes that the CBO shouldn’t be trusted to measure revenue from the OBBBA, he trusts their tariff-revenue projections of $2.8 trillion. Tariffs suppress real GDP growth and are likely to generate lower income and payroll tax receipts, which will partially offset the tariff revenue—dynamic effects not fully captured in headline figures. In addition, it is interesting to see a supply-sider like Kudlow highlight the revenue from tariffs as a positive thing. They are a tax increase on the American people. So, effectively, he is rejoicing in paying for this bill with taxes on us consumers.

Further, these tariffs are not included at all in OBBBA; they are a unilateral tax hike from the President. Given that, this revenue projection can be increased, reduced, or even entirely wiped out at any moment barring legislative action from Congress. If Kudlow (or Congress) wants to take credit for the President’s tax hike then Congress should vote on it.

Conclusion

I am sorry to say that Larry Kudlow’s optimistic claim that the One Big Beautiful Bill (OBBBA) will not only pay for itself but will reduce the deficit by $8.5 trillion doesn't hold up under scrutiny. His reliance on inflated revenue projections, particularly the notion of a $4 trillion growth dividend from a sustained 3% GDP increase, ignores credible economic forecasts and the structural weaknesses embedded in OBBBA itself. While pro-growth tax cuts can eventually offset revenue losses, OBBBA’s provisions—such as expanding low-growth tax expenditures, raising the SALT deduction, and short-term extensions of key growth drivers—undermine any substantial economic boost.

Moreover, Kudlow’s selective trust in the CBO’s tariff-revenue projection ignores the negative economic impacts of tariffs, which suppress growth and function effectively as taxes on American consumers. The flawed approach of simultaneously counting on high tariff revenue and robust economic growth is contradictory and economically unrealistic.

Ultimately, genuine fiscal responsibility requires realistic assumptions, disciplined spending cuts—not merely reductions in growth—and reforms that truly broaden the tax base and encourage investment. OBBBA, despite some beneficial elements, falls short on these crucial measures.