Sound Money or Digital Detour?

Evaluating Stablecoins Against the Triple Test of Exchange

Stablecoins aim to combine the efficiency of blockchain-based settlement with the reliability of traditional money. Initially developed as a means for crypto traders to move funds between exchanges without exposure to volatility, stablecoins have since evolved into multi-purpose financial instruments: tools for payments, cross-border transfers, digital collateral, and even potential foundations for future financial infrastructure.

Their rapid rise raises a question: Are stablecoins the next step in the evolution of money, or a modern echo of money’s oldest flaws? To some, stablecoins represent the long-awaited bridge between private innovation and public trust. To others, they are privately issued promises that cannot replicate the core properties of sovereign money and risk undermining financial stability and monetary control. The answer may lie less in the nature of stablecoins themselves than in the institutional frameworks that govern money and the economic rents those frameworks sustain.

The BIS Case Against Stablecoins

The stablecoin debate has been intensifying as central banks, regulators, and research institutions have begun to draw clearer lines between tokenized innovation and monetary sovereignty. Among them, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) has made it clear in its Annual Economic Report (June 2025) that it does not consider stablecoins suitable as systemic money:

“Society has a choice. The monetary system can transform into a next-generation system built on tried and tested foundations of trust and technologically superior, programmable infrastructures. Or society can re-learn the historical lessons about the limitations of unsound money, with real societal costs, by taking a detour involving private digital currencies that fail the triple test of singleness, elasticity and integrity.”

Firmly concluding that stablecoins cannot meet these criteria, the BIS dedicates a full section of its report to warning about the consequences and side effects of systemic stablecoin use. These include :

fragmentation of the monetary system into parallel circuits of private and public monies,

the absence of a lender of last resort or deposit insurance,

risks of regulatory arbitrage, and

the procyclical behavior of coins whose supply contracts precisely when liquidity is most needed.

The BIS also underlines the loss of monetary sovereignty in countries that adopt stablecoins backed by foreign currencies, as well as the erosion of domestic policy control in countries that issue locally backed stablecoins, where the link between reserves and government debt could lead to fiscal dominance. Despite acknowledging the possibility of mitigating these risks through regulation, the BIS stands firm: Privately issued stablecoins are unsound money. Instead, recognizing innovation potential and the existing benefits of digital currencies, the BIS pleads for a full tokenization of central bank currencies (CBDCs) and commercial bank deposits, as well as government securities, thereby modernizing — but ultimately preserving — the existing two-tier, centralized, banking system.

An Alternative View: Stablecoins as Tokenized Money

While the BIS presents stablecoins as inherently flawed, other analyses take a more optimistic view. Notably, a recent report entitled Mind the Gap: How Stablecoins Can Secure the UK’s Financial Future (September 2025), published by the Centre for Financial Technology and the Centre for Cryptocurrency Research and Engineering at Imperial College Business School, examines many of the same risks identified by the BIS and yet views stablecoins as a viable form of tokenized money able to complement the existing system rather than disrupt it, provided they operate under a “well-calibrated regime.”

Stablecoins should be recognised not merely as a payments innovation but as part of the wider category of tokenised money, with implications for financial stability, monetary sovereignty, and government debt markets. [...] Stablecoins will not replace banks or public money, but they are set to complement them as an integral part of modern financial infrastructure. The challenge for policymakers is to integrate them in ways that safeguard resilience, protect consumers…

Testing Stablecoins Against functions of Money

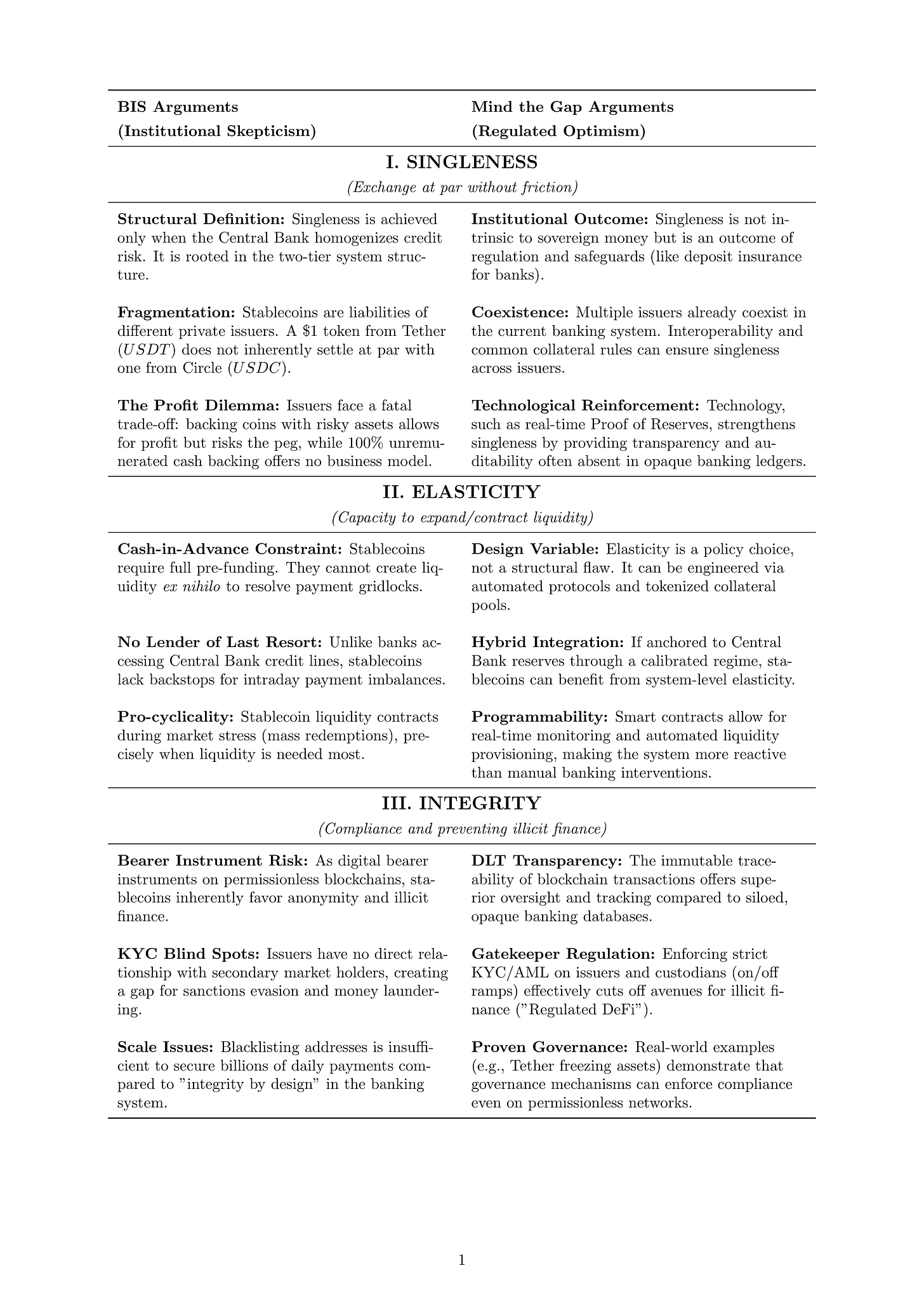

Let us focus on both reports’ assessment of the ability of stablecoins to meet the following criteria of money: singleness, elasticity, and integrity.

Singleness: Can Private Money Trade at Par?

The BIS adopts a structural and institutional definition of singleness rooted in the two-tier monetary system, where all payments clear at par through central bank reserves. Singleness, in this view, is achieved because the central bank homogenizes credit risk by providing the ultimate settlement asset. For stablecoins though, tokens are a liability of multiple private issuers. Transfers do not then settle through the central bank balance sheet but rather circulate at varying exchange rates amongst one another even when pegged to the same currency. A dollar coin emitted by Tether (USDT) for instance, cannot be traded at par with a dollar coin emitted by Circle (USDC). These exchange rate frictions introduce fragmentation within what should be a single unit of account, tradable at par no questions asked.

Apart from this inter-issuer fragmentation, there is also a difficulty for coins to follow the “real world” currency they are supposed to be pegged to. In that regard, the BIS highlights the “inherent tension between stablecoin issuers’ ability to fully uphold their promise of stability and their pursuit of a profitable business model.” Indeed, if the coins they issue are backed by assets presenting some credit or liquidity risk, they will earn returns but risk losing the peg as holders lose the trust in the issuer’s capacity to redeem at par in case of high redemption demand. On the other hand, if coins are fully backed by unremunerated Fiat reserves, the only profit to be made is payment fees, which isn’t a promise for a great business model.

The Mind the Gap report challenges this view. First, it views singleness as a spectrum more than an “absolute standard” mentioning “fees, access costs, and acceptance differences” already bending the notion of singleness within the existing system where routinely exchanges between commercial bank money, e-money and cash do not happen without friction. Singleness is viewed as an institutional outcome emerging from regulation and credible redemption frameworks. Historically, the uniformity of money has always relied on policy instruments that sustain confidence, such as deposit insurance or lender-of-last-resort facilities, more than on the nature of the monetary instrument itself. The authors claim stablecoins can preserve stability if they are fully backed by safe and transparent assets and integrated into settlement mechanisms that ensure redemption at par. In such settings, singleness would not stem from the stablecoins’ intrinsic characteristics but from the system-level safeguards that support their convertibility, just as commercial bank deposits preserve par value only through prudential regulation. Stablecoin unpegging is seen as a symptom of deficient institutional anchoring, not of the private nature of the instrument.

As for the fragmentation between issuers, Mind the Gap rejects the idea that the coexistence of several stablecoin providers necessarily implies a loss of singleness. Multiple issuers already exist in today’s monetary system: each commercial bank issues its own liabilities. Yet these coexist fine because regulation and infrastructure enforce one-to-one convertibility through central bank settlement. In the same way, differences between USDT and USDC would not create “two parallel currencies” if both were subject to common rules ensuring full-reserve backing, par redemption, and interoperability across networks.

The authors go farther and note that technological advances such as real-time Proof of Reserves, automated redemption via smart contracts, and cross-chain settlement could even strengthen singleness by providing continuous, auditable assurance of solvency and liquidity generating a degree of transparency largely absent from traditional banking systems.

Elasticity: Liquidity in Times of Stress

The elasticity of a monetary system refers to its ability to expand and contract the supply of settlement assets flexibly enough to meet payment needs and prevent gridlock. In the two-tier architecture, this elasticity is partly enabled by the central bank, which can extend intraday or overnight credit against collateral, thereby ensuring that obligations are discharged in real time without each participant having to pre-fund transactions. Stablecoins, in contrast, operate under a cash-in-advance constraint: Every token must be fully backed before issuance, and settlement occurs only once funds have moved on the blockchain. Because issuers cannot create or destroy liquidity on demand, the system cannot respond elastically to shocks or payment imbalances. The BIS argues that this rigidity would amplify in times of market stress, precisely when liquidity is most needed, as stablecoin liquidity tends to contract with stress due to mass redemptions.

The Mind the Gap report takes the opposite stance, framing elasticity not as a fixed structural property of sovereign money but as a design and policy variable that can be engineered within a properly regulated digital framework. It argues that in practice, elasticity is only the result of institutional mechanisms such as central bank credit lines, deposit insurance, or prudential regulation. By the same logic, a well-designed stablecoin regime could replicate this flexibility through automated redemption protocols, tokenized collateral pools, and programmable credit arrangements that adjust supply in response to transactional demand. The report highlights that technology and transparency can in fact enhance elasticity: On-chain proof-of-reserves and interoperable settlement platforms can enable real-time monitoring of backing assets and instant liquidity provisioning between issuers. In its view, what the BIS interprets as a structural constraint is really, again, just a regulatory and choice.

Integrity: Financial Crime and Trust by Design

The BIS posits that stablecoins compromise the integrity of the financial system due to their nature as digital bearer instruments on permissionless blockchains. The report mentions that pseudonymity of public ledgers allows users to hide behind wallet addresses, making stablecoins a “go-to choice” for illicit finance, sanctions evasion, and money laundering. Unlike the two-tier banking system, where intermediaries are legally obligated to perform know-your-customer (KYC) checks on account holders, stablecoin issuers often have no direct relationship with secondary market holders and cannot verify identities. The BIS warns that relying on blockchain analytics or “blacklisting” addresses is insufficient to scale for billions of daily payments, contrasting this with the “integrity by design” offered by tokenized deposits on a unified ledger.

Conversely, Mind the Gap argues that the transparency of distributed ledger technology (DLT), compared to traditional systems, can actually enhance financial integrity. Notably, the report shows that stablecoins offer on-chain Proof of Reserves and traceable transaction flows that improve visibility into asset movements, which are opaque in conventional banking. Also, just like for singleness and elasticity, rather than viewing pseudonymity as a flaw, the authors push for enforcement of KYC/AML rules on stablecoin issuers and custodians to cut off illicit finance. In this sense, Tether has successfully frozen assets linked to illicit activity, thereby demonstrating that governance mechanisms can override the immutability of the blockchain to enforce compliance.

Institutions, Incentives, and Innovation

In the end, the BIS conservatively points out the weaknesses of stablecoins as a systemic payment instrument. Mind the Gap methodically demonstrates that all these flaws are actually traits that all means of exchange can either bear or not, depending on the regulatory framework they evolve in. Questioning the technical feasibility of private stable currencies already seems outdated. Private payment means are possible.

Banks are naturally very bearish concerning systemic use of stablecoins. As the 2025 Nobel laureates in economic sciences remind us: Beneficiaries of economic rents have a strong incentive to preserve them and often do so by resisting innovation that threatens existing arrangements. But the business of owning a vault led to the business of spread earnings on the two-tier system, and tomorrow could lead to something else. Banks are not in existential danger, they just might be forced to compete, which, once in a while, cannot hurt…

Exceptional breakdown of the institutional arguments around stablecoins. The Mind the Gap pushback on BIS's singleness critique is particularly sharp because it exposes how current banking already tolerates fragmentation through fees and access differences. The elasticity issue feels less about technological limits and more about preserving central bank control over credit creation. I worked brieflywith fintech startups last year and saw how compliance frameworks could absolutely be adapted to digital rails without sacrificing integrity or policyflexibility.

Great post, thanks. It sounds like Mind The Gap arguments expose the fact that Stablecoins are very high risk, unless new regulations are introduced that explicitly include and protect them within the existing banking system.

The banking system does not need a new “digital dollar.” What is needed is a national payments “highway” that gives both merchants and their customers real-time access to their bank accounts, eliminating intermediaries and third-party processing fees. Stablecoins are intermediaries that will cost merchants a percentage of the Stablecoins value to convert back into dollars.

The dollars in your bank account are already “digital” in the form of a number representing the total balance in your account. Your account exists in a digital ledger at your bank.

Stablecoins are not a solution they are a symptom. Our national leaders in Congress, and especially in our Commerce and Treasury departments, have failed to recognize the need for a national real-time payment system for the U.S. dollar.

An example of a national payment system is proposed in a book titled: The MAFIA paradigm

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0FSZ2QMKV