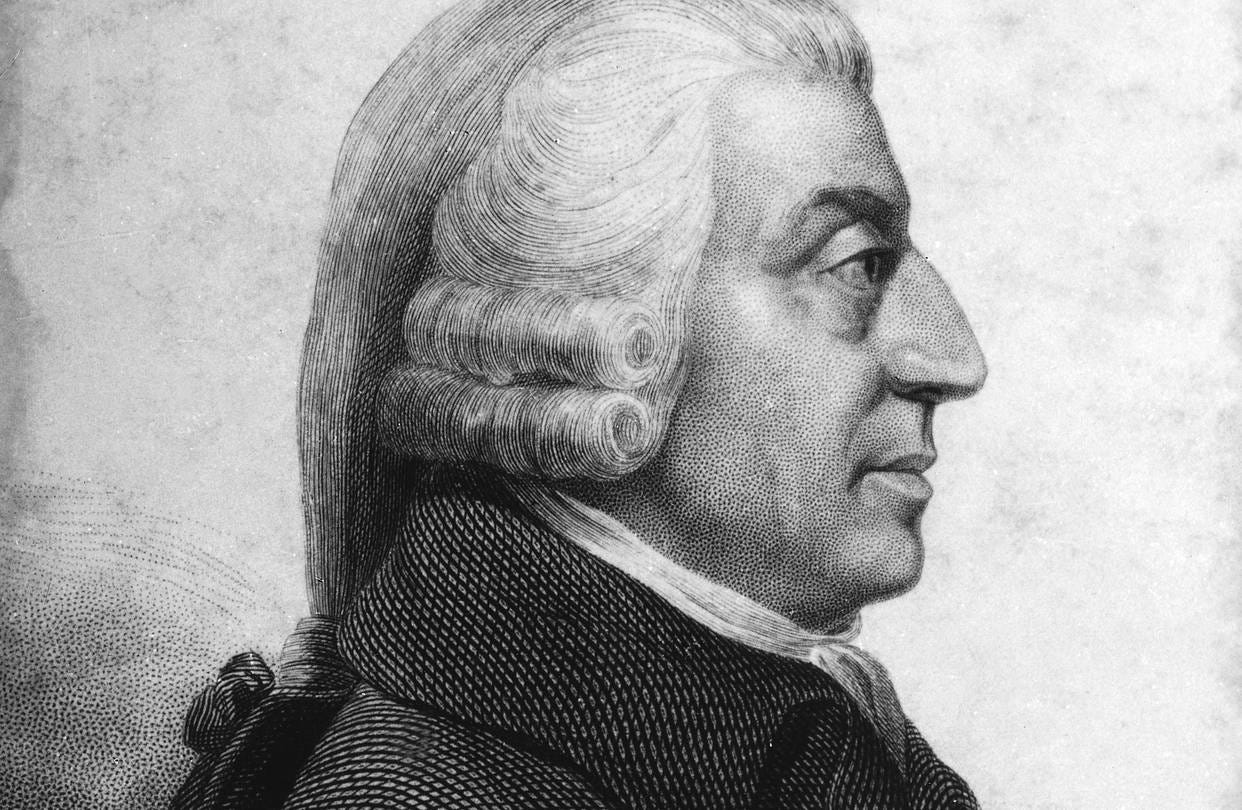

Studying the Wealth of Nations (Part 5)

Smith's Folly on Interest Rates

This is the fifth part of a weekly project marking the 250th anniversary of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations. You can find the third installment here.

I don’t remember much from my brief undergraduate study of The Wealth of Nations, but I do remember being appalled by Adam Smith’s proposal to fix interest rates.

Rereading those passages in Chapter IV of Book II, however, I was pleased to discover that Smith’s analysis of interest rates was far more sophisticated than I had remembered—which makes his ultimate support for interest rate controls all the more puzzling.

He begins with a sharp takedown of countries that ban interest altogether. Because something can always be “made by the use of money,” he argues, “something ought every where to be paid for the use of it.” Attempts to prohibit interest do not eliminate it; they merely drive it underground. As Smith observes, such regulation “instead of preventing, has been found… to increase the evil of usury,” since borrowers must compensate lenders not only for the use of funds but also for the legal risk involved.

He then turns to the difficulty of setting interest rates by law.

Set them too low and “honest people, who respect the laws of their country” but have imperfect credit will be shut out of the market. Set them too high and “the greater part of the money…would be lent to prodigals and projectors, who alone would be willing to give this higher interest.”

While insightful, Smith blurs what we would today call a price ceiling and a price floor. He worries about an interest rate set too high blocking prudent borrowers who would borrow only at lower rates—a price floor problem. Yet he also worries about a rate set too low excluding trustworthy borrowers who qualify only slightly above the legal maximum—a price ceiling problem.

Despite recognizing those distortions, he concludes that the legal interest rate “though it ought to be somewhat above, ought not to be much above the lowest market rate.” In other words: impose a ceiling, but place it just above the lowest rate already observed in the market.

But I confess I’m puzzled why Smith felt any need to propose such a policy in the first place. He clearly commanded a strong understanding of supply and demand, and his reference to a “lowest” market rate implies the existence of higher rates reflecting differences in borrower risk. If the market was already pricing risk accordingly, what problem remained for the law to solve?

The laissez-faire recommendation one would expect from Smith would have allowed lending to any type of borrower—trustworthy or not, for consumption or investment—with the interest rate adjusting to reflect the differences in risk.

My sense is that his moral views on usury, which he regarded as “evil”—especially when the borrowing was for immediate consumption—clouded his economic judgment: “The man who borrows in order to spend will soon be ruined, and he who lends to him will generally have occasion to repent of his folly.”

But he may have also been offering a second-best solution, given political realities. As he states, “In countries where interest is permitted, the law, in order to prevent the extortion of usury, generally fixes the highest rate which can be taken without incurring a penalty.” An alternative explanation, then, is that he was describing best practice in a world where interest ceilings were politically inevitable.

Regardless of the reason, his proposal remains an unfortunate blemish in an otherwise excellent analysis.

Bonus Quote: Drunkenness

Smith also anticipates a broader principle about regulation:

“It is not the multitude of alehouses, to give the most suspicious example, that occasions a general disposition to drunkenness among the common people; but that disposition arising from other causes necessarily gives employment to a multitude of ale-houses.”

Supply does not create demand out of thin air. Where there is a demand or “disposition,” supply will emerge—legally or otherwise. That was true for interest in Smith’s time, for alcohol during Prohibition, and for drugs and prostitution today.

Bonus Quote #2: Trade

In Chapter I of Book III, Smith opens with an extraordinary exposition on the benefits of trade, focusing his analysis on exchange between the inhabitants of a town and those in the country. While I highly recommend reading the entire opening paragraph of that chapter, two sentences stood out:

The town affords a market for the surplus produce of the country… and it is there that the inhabitants of the country exchange it for something else which is in demand among them. The greater the number and revenue of the inhabitants of the town, the more extensive is the market which it affords to those of the country; and the more extensive that market, it is always the more advantageous to a great number. (emphasis added)

Protectionists would have us believe it is a bad thing when our trading partners get richer, implying that we are necessarily getting poorer. Smith understood what many still miss: trade is not a zero-sum contest but a mutually beneficial exchange—prosperity abroad expands opportunity at home.