Studying the Wealth of Nations (Part 3)

Thoughts on Guilds, Past and Present

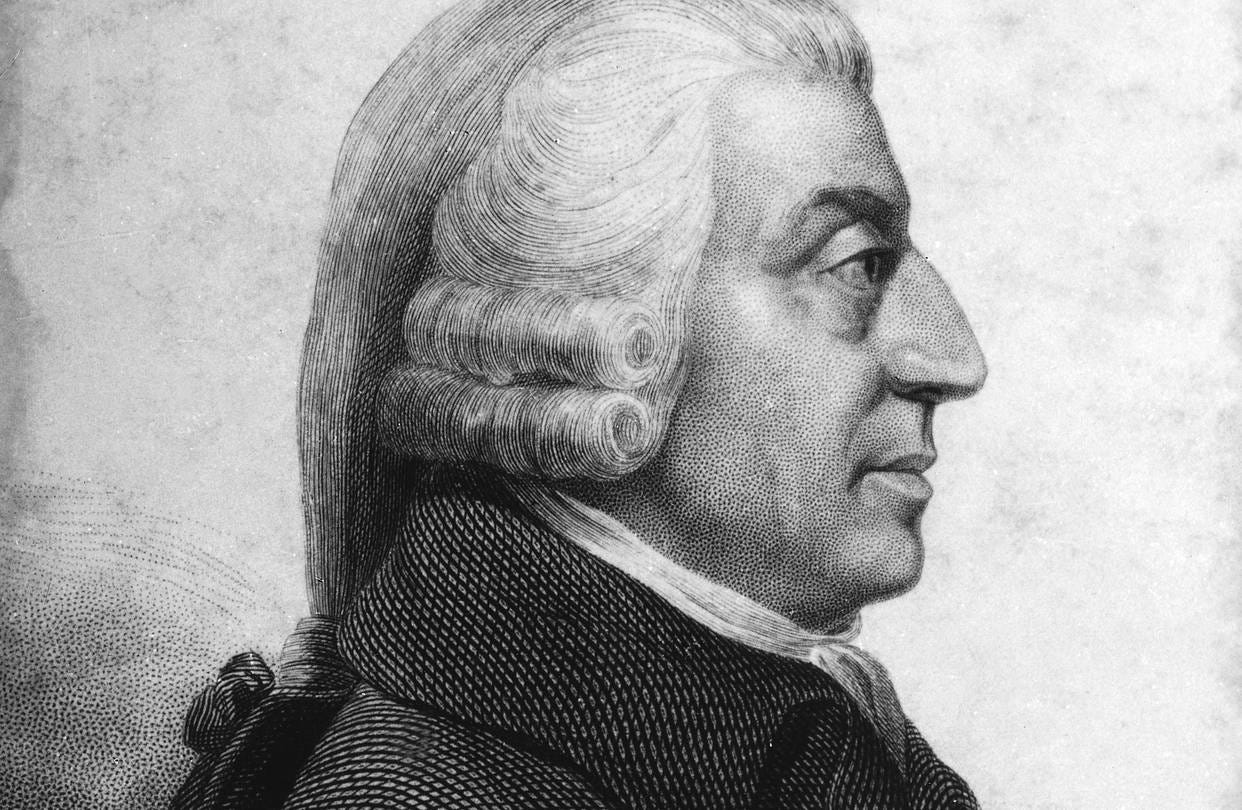

This is the third part of a weekly project marking the 250th anniversary of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations. You can find the second installment here.

In his essay “What Should Economists Do?”, the late Nobel laureate James Buchanan distinguished between two approaches to economics. One, employed by both Smith and Buchanan, treats economics as “the theory of markets,” rooted in man’s “propensity to truck, barter, and exchange.” The other, now dominant, treats economics as a “theory of resource allocation”: a largely mathematical exercise in equilibrium and optimization.

It is this former approach, I would argue, that makes Smith’s analysis so enduringly informative. By treating markets as social institutions rather than abstract systems, Smith was able to explain not just prices and quantities, but also the human elements entangled throughout process.

Among the institutions he examined closely were those intervening in European labor markets. He identified three broad categories: policies that increased competition beyond what would otherwise exist in an industry; policies that obstructed the movement of labor and capital; and, most interestingly, policies that restricted competition outright—namely, guilds, or as he called them, “incorporations” (not to be confused with the modern business corporation).

A guild is an organization of industry professionals that unite to restrict competition for the purpose of increasing their wages. Smith noted three ways they did so: first, by requiring an apprenticeship before entering an industry; second, by restricting the number of apprentices that a master could take; and third, by dictating the number of years that an apprentice was required to serve.

To my surprise, Smith explains that the original Latin name for incorporations was universities—hence the “university of smiths, the university of taylors, &c.” Our modern centers of higher education appear to have adopted not only the name of these ancient guilds, but also their time requirements and much of their language:

When those particular incorporations which are now peculiarly called universities were first established, the term of years which it was necessary to study, in order to obtain the degree of master of arts, appears evidently to have been copied from the term of apprenticeship in common trades… As to have wrought seven years under a master properly qualified, was necessary, in order to intitle any person to become a master… teacher or doctor (words antiently synonymous) in the liberal arts.

We, of course, still have modern-day guilds. Every few years we hear of strikes from one of the Hollywood guilds—the Screen Actors Guild, the Directors Guild, or one of the various Writers Guilds. But we also have guilds for lawyers through bar associations, for realtors through the National Association of Realtors, for truckers through the American Trucking Associations, and for physicians through the American Medical Association (AMA), among many others.

Consider the AMA. Fifty years after its founding, one of its prominent early leaders, Nathan Smith Davis, offered a brief history of its origins. He notes that at the end of the eighteenth century there were only four medical colleges in the United States, with a combined annual attendance of fewer than three hundred students, and “not more than fifteen annually received the degree of Doctor of Medicine.”

By the time of the AMA’s formation in the mid-nineteenth century—and as a consequence of the country’s rapidly growing population—the number of medical schools had risen to “more than thirty, with an annual attendance of more than 3,500 students, of whom not less than 1,000 annually received the degree of Doctor of Medicine.” This expansion was possible because “several States freely granted charters for medical schools,” whose diplomas functioned as licenses to practice. The result was a “rivalry for numbers of students,” which led to competition in both tuition and the duration of education.

To address this problem, a nationwide convention of “all the medical societies and colleges in this country” was held in May 1840. The failure of that convention—and of those that followed—was acknowledged in the concluding resolution of the 1845 convention, which stated that “there is no mode of accomplishing so desirable an object [elevating the standard of medical education] without concert of action on the part of the medical… institutions of all the States.” Acting unilaterally, it was feared, would merely divert students from compliant schools to those that refused to raise standards.

Eventually, the AMA succeeded. Davis concluded that each of the organization’s original goals had been accomplished:

Universal free and friendly social and professional intercourse has been established; the advancement of medical science and literature in all their relations has been promoted; and the long agitated subject of medical education has reached the solid basis of a fair academic education as preparatory, four years of medical study, attendance on four annual courses of graded medical college instruction of from six to nine months each, and licenses to practice to be granted only by State Boards of Medical Examiners.

The AMA thus provides an excellent illustration for three of Smith’s insights. First:

People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.

Second:

In a free trade an effectual combination cannot be established but by the unanimous consent of every single trade, and it cannot last longer than every single trade continues of the same mind

And third:

The clamour and sophistry of merchants and manufacturers easily persuade them [non-guild members] that the private interest of a part, and of a subordinate part of the society, is the general interest of the whole.

It’s reasonable to object that the AMA is a special case—that a guild may be necessary to raise the quality of doctors and improve public health, making its restrictions genuinely “in the general interest of the whole.” It is likely true that American physicians are better trained than they otherwise would be. But it is also true that the AMA has historically lobbied to restrict the entry of qualified international doctors, to prevent nurses and nurse practitioners from providing services without physician supervision, and to restrict government funding for medical residencies—a bottleneck the AMA itself helped create. Perhaps most egregiously, it gaslights the public about the physician shortage it exists to produce, while simultaneously petitioning Congress for more subsidies.

One recent policy proposal that politicians appear not to fully understand is increased price transparency in healthcare, a major pillar of President Trump’s recently proposed “Great Healthcare Plan.” Requiring medical providers and insurers to publicly disclose their rates, prices, and fees would undoubtedly provide consumers with more information. But it would also make that information more easily accessible to other healthcare professionals and to the AMA itself, facilitating the monitoring and enforcement of cartel discipline. It is therefore unsurprising that an organization founded to reduce medical competition would advocate for such measures.

While Smith does not explicitly connect guilds to price transparency, he does connect them to public name registers:

A regulation which obliges all those of the same trade in a particular town to enter their names and places of abode in a publick register, facilitate such assemblies. It connects individuals who might never otherwise be known to one another, and gives every man of the trade a direction where to find every other man of it.

The effect is similar. Cheating guild members—and non-members—can increase profits by offering lower prices. By mandating public registers or price transparency, the government makes it easier for guilds to identify and discipline nonconformists.