Taking Steps Toward a Fusion Future

Policymakers should allow innovation within energy markets and minimize the regulation of nuclear fusion

For nearly 75 years, we’ve been told that we are just 30 short years away from functioning nuclear fusion reactors. These artificial stars, formed by smashing atoms together to create heavier particles, come with the promise of a sustainable, clean, nearly limitless energy source with very few drawbacks. And now, more than ever, those 30 short years seem as though they may finally be ticking away. Perhaps nuclear fusion really is on our doorstep, poised to become the energy source that brings humanity into a new age.

But with all innovation and development comes the classic question of how the government should interact with a new technology to properly facilitate its growth without stifling progress. Should nuclear fusion be regulated in similar ways to fission (the process that created the atomic bomb) to avoid excess radiation, private weapons access, or meltdowns? Or is fusion something else entirely, a less dangerous process that can be widely used with relative safety?

How Dangerous Is Nuclear Fusion?

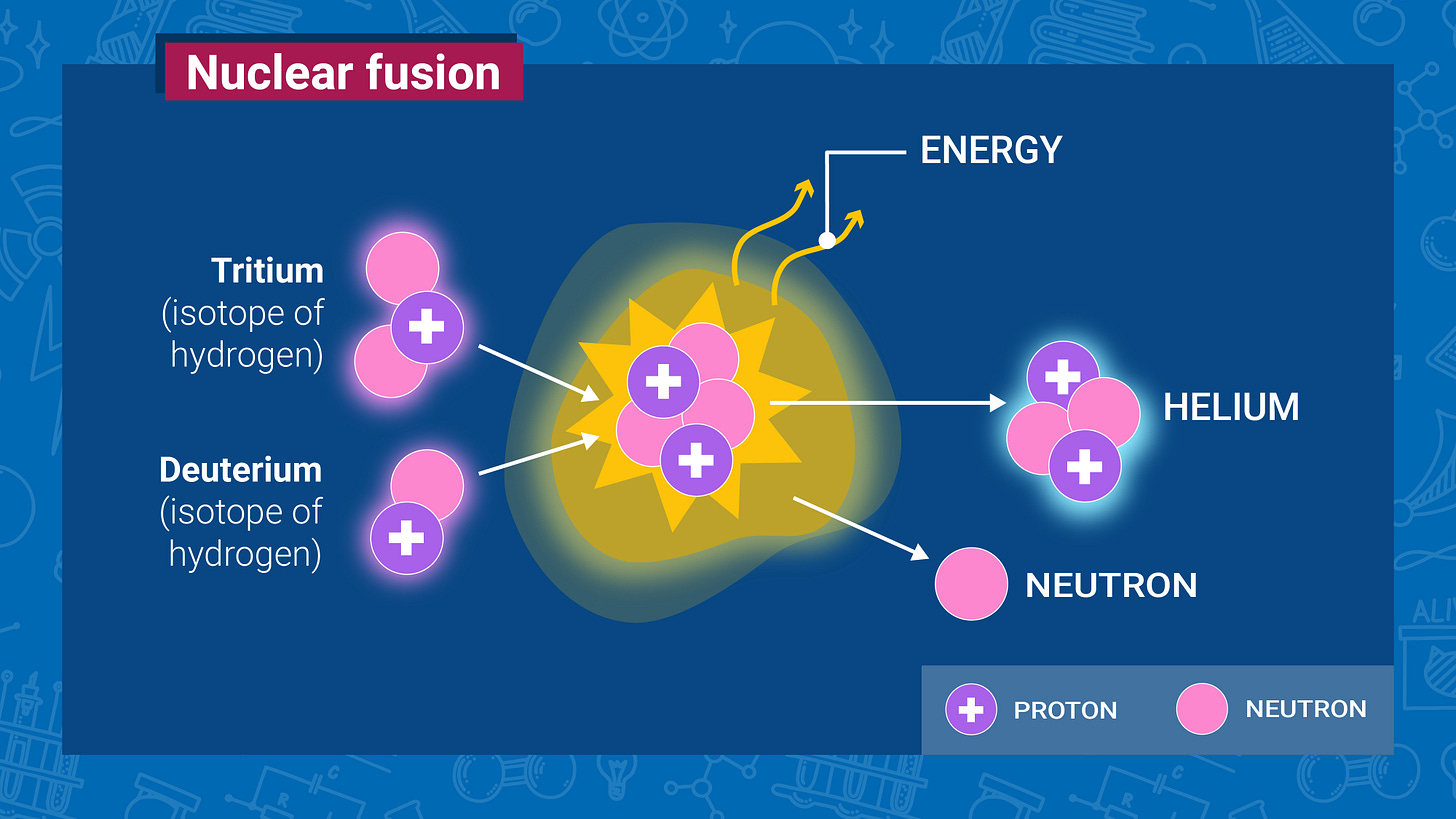

The most common argument for the stringent regulation of nuclear fusion is safety, but in simple terms, fusion is quite safe. Unlike fission, which relies on taking heavy, radioactive elements and breaking them apart, fusion takes low-energy particles, isotopes of hydrogen called deuterium and tritium, and smashes them together to create helium and an extra neutron, as seen in the image below. The process requires a particle accelerator, meaning it isn’t a sustained chain reaction like those found in fission reactors.

Tritium is considered a low-level radioactive hazard, but before this raises warning flags to the nuclear nay-sayers, it is naturally occurring and can only cause damage to humans if it is actively ingested. The beta particles that tritium emits cannot pierce skin, and if they are not ingested, they have no way to interact with your body. Additionally, the lack of a sustained reaction in the fusion process means that there is no meltdown risk. If the reactor fails, then the particle accelerator that is creating the fusion reaction will stop, as will the process.

The bigger concern people often have when it comes to nuclear fusion is the possibility of disseminating the materials and knowledge to the public, who can then use them to build thermonuclear weapons. This is a terrifying idea, but luckily, it isn’t relevant to the question of nuclear fusion as a source of energy. While it is true that thermonuclear weapons use fusion, they don’t use only fusion. They are two-stage bombs, with the primary ignition being activated by a traditional atomic, or fissile, warhead. This warhead then triggers the fusion reaction, which sparks a larger explosion. Thus, a pure fusion reactor could not in any known way be repurposed to become a thermonuclear warhead.

How Should Policymakers Proceed?

There are two common policy approaches to innovative private markets. The first is known as the precautionary principle, which is the idea that the government should come in and regulate private businesses before they can do significant harm. An example of this principle in practice is how nuclear fission was handled in the U.S., being initially highly regulated and only later opened up to private use. The second is known as permissionless innovation. This is the idea that the government should let industries run free, for lack of a better term, and discover where there is a need for oversight only after the innovation is implemented. An example of this principle would be the internet, which is only now seeing discussion on how it interacts with rights guaranteed by the First Amendment, privacy laws, and more.

Arguments in favor of the precautionary principle are typically based on risk-averse attitudes. Those who subscribe to this view weigh the costs of innovation much more highly than the benefits, leading to policies that do a large amount of work to avoid relatively small problems. Permissionless innovation, by contrast, is typically embraced by entrepreneurs, and while it doesn’t come without issues, it does lead to a higher degree of growth in an industry. Choosing between these two approaches often comes down to perceived risk, and since fusion is both incredibly safe and clean, a “precautionary principle” approach has little if any justification.

A Fusion Future

As of 2024, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) regulates the materials necessary for fusion. Additionally, the ADVANCE Act creates precedent for further fusion regulation in the United States. If this trend continues and the NRC gets its hands on the entire process of nuclear fusion, then regulation will likely create large barriers to both entry and innovation within the realm of fusion, similar to what happened with fission. Perhaps this doesn’t sound like a problem. What’s the harm of having one more stagnant energy industry?

Under the right circumstances, nuclear fusion wouldn’t just be a fantastic energy source; it would also bring us to a more abundant future. With proper implementation, fusion is not only one of the most energy-efficient generation methods possible—as much as four million times more efficient than fossil fuels or natural gas per kilogram of fuel—but it is also incredibly sustainable given the large amount of hydrogen and small atoms in the universe. Abundance of resources drives growth in miraculous ways, and just as food surpluses in river valleys brought about a new era of human civilization, so, too, can energy abundance.

While it is true that the exact costs and benefits of fusion are unknown, current research and development are promising, and the scientific consensus seems to be that fusion would provide us with a peerless source of energy. To explore these possibilities and see a world with greater energy abundance, it is imperative that we allow for a space for fusion to grow and develop, free from overregulation and overcautious attitudes. Only by taking risks, trying new things, and learning from our mistakes will we arrive at a fusion future.

Should the possession of Tritium be regulated at all?