The Case Against an International Panel for Inequality

Why the Crisis Narrative Doesn’t Match the Evidence

Last month, French economist Thomas Piketty and others called on world leaders to promote a new idea: an International Panel on Inequality modeled after the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The initiative was recommended by the G20 Committee of Independent Experts on Global Inequality, led by Columbia professor and Keynesian economist Joseph Stiglitz.

The framing of this proposal positions inequality not as an economic indicator, but as a global crisis requiring coordinated international action. The advocates of this proposal also make the normative claim that a more equal world — in terms of income and wealth distribution — is the foundation of a “successful future,” the end goal being to shift the global policy consensus toward viewing inequality reduction as a top priority that requires aggressive state intervention backed by an expert body to legitimize such efforts.

I want to be generous and give the benefit of the doubt to some of the signatories of this proposal who have, for example, endorsed the economic agenda of the Chavez regime in Venezuela. But even setting those credibility concerns aside, the proposal itself suffers from several analytical flaws that make its conclusions difficult to take seriously.

First, inequality measures (Gini coefficients, top income and wealth shares, and similar metrics) are welfare-incomplete and highly sensitive to measurement choices and to missing non-income dimensions of well-being. For the poorest in society, income growth is the dominant driver of living standards. As a result, who is “better off” depends much more on overall development than on modest differences in inequality. Cross-country differences in living standards are best explained by institutions, property rights, the rule of law, levels of corruption, and broader economic freedom.

Second, it is important to recognize that global income inequality trends have been moving in a positive direction for decades. Global income inequality is now at a 50-year low, while global wealth inequality is at an all-time low. Yes, you read that correctly — but you might not hear this inconvenient truth from the advocates of this proposal.

Ironically, these global trends can be illustrated using data compiled by French economists Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman (the PSZ approach). Figure 1 below shows global wealth and income shares for the top 10%.

The share of wealth held by the top 10% has been in slow decline for over a century: It peaked at 83% in 1910 and fell to 74% by 2023. Meanwhile, the income share of the top 10% shows a similar pattern. It peaked at about 59% in 1910, declined during the post-war period to about 50%, rose again in the 1980s and 1990s, and then fell in the 21st century to about 53% today. By contrast, the bottom 50% now holds its highest share of both income and wealth in more than seven decades.

Third, as I have documented in previous pieces, economists who make bold claims about inequality often use methodology with serious shortcomings. For example, Piketty and Saez (PS data) often claim that the top 1% of households control over 40% of all wealth in the United States. Their method infers wealth by capitalizing income reported on tax returns, even though tax return data are incomplete and unevenly distributed.

Not all forms of wealth generate taxable income, and when they do, returns can vary widely even for assets of similar value. Some investments are deliberately structured to minimize taxable income, while others produce returns that are difficult to attribute accurately to underlying wealth. These mismatches lead to serious distortions in the resulting estimates.

Existing research further challenges the narrative of extreme concentration. One NBER paper published in 2021 improves on the PSZ approach by incorporating more accurate estimates of fixed-income investments, pass-through business wealth, corporate equity, housing, and pensions. The resulting estimate for the top 1 percent’s share of total wealth hovers around 31%, or about 10 percentage points below the Zucman estimate.

Importantly, these estimates do not include Social Security wealth, which constitutes a large portion of lifetime savings for most households. While private accounts, pensions, and home equity are routinely included in wealth estimates, the current value of Social Security benefits is often ignored. Yet its omission paints an artificially bleak picture of wealth inequality.

According to the CBO, when Social Security wealth is factored in, the share of wealth held by the top 1% increased only modestly, from 23% in 1989 to 27% in 2022. A recent study published in the Journal of Finance offers a similar finding: In 2019, the top 1% held just under 24% of total wealth, up from 22% in 1989. Again, these figures stand in stark contrast to the headline-grabbing figures pushed by Gabriel Zucman and coauthors.

Moreover, revisions of income concentration estimates by economists Vincent Geloso, Phillip Magness, and their coauthors correct serious errors in the original PS data. The authors include misclassifications, improper assumptions about returns, and failure to account for structural economic changes since the 1980s. These corrections further reduce the apparent rise in wealth concentration over recent decades.

Then there is the issue of within-country measures of wealth inequality. In this field, the chief advocates for a global inequality panel have their own metrics and database that they champion as first class. As they note, “We have built the World Inequality Database (WID), the most comprehensive and up-to-date resource for measuring and tracking inequality globally.” The only issue is that the WID is fundamentally flawed.

The WID relies on a mix of tax data and household survey data. While tax data is quite reliable for most developed countries, it is sparsely available for many less-developed countries. For example, only 1–2% of tax unit data for large countries such as China and India may be available (Chancel and Piketty, 2019; Piketty, Yang and Zucman, 2019). Therefore, the WID relies heavily on household surveys to fill in these gaps.

Empirical analysis of these household surveys finds that poorer households underreport, and the scale of misreporting has been getting worse over time. After correcting for underreporting, the authors find that global inequality and poverty are lower and fall faster than WID and World Bank PIP data suggests.

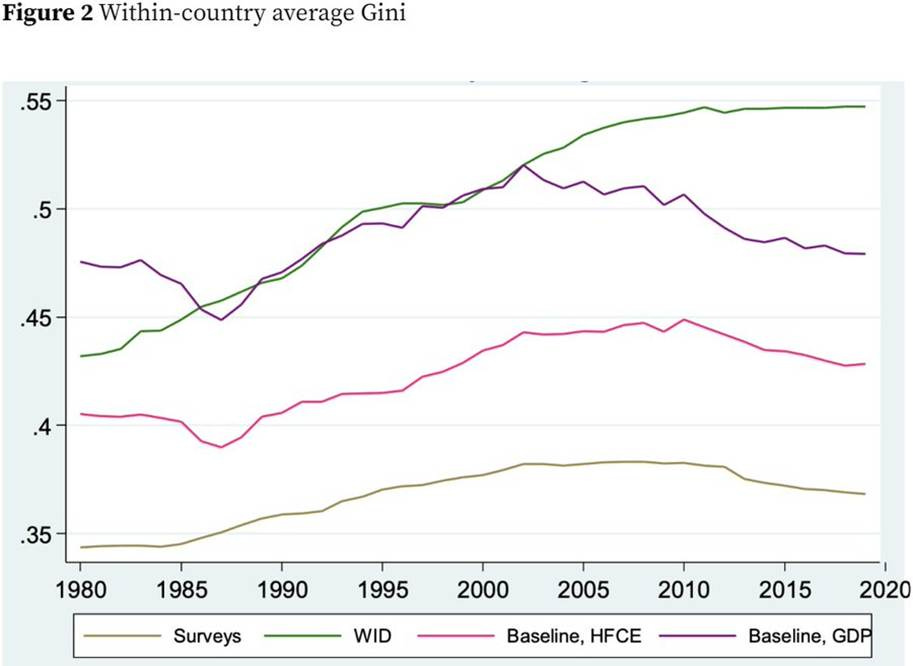

Not only has overall global inequality fallen, but within-country inequality has stopped rising and has been falling for the better part of a decade, if not more. As the figure below demonstrates, inequality within countries according to a range of measures has declined since the early 2000s.

Taken together, these methodological and data issues complete the third major weakness in the case for a global inequality panel: the fact that the world is doing much better than we thought, not only at eliminating extreme poverty and reducing the $2.15-a-day headcount ratio, but also at reducing poverty at higher poverty lines ($3.65 a day and $6.85 a day). As the figure below highlights, poverty rates at these higher thresholds have declined to 30% and 50%, respectively, of their 1990 levels for the world distribution of disposable income or consumption, which is considerably lower than World Bank household-survey-based estimates alone.

Considering the evidence, the call for an International Inequality Panel modeled on the IPCC rests on a fundamentally flawed diagnosis. Inequality is neither spiraling out of control nor threatening the foundations of global prosperity; by every credible measure, both global income and global wealth inequality have been declining for decades. What disparities remain are better explained by institutions, property rights, corruption, governance quality, and economic freedom than by abstract distributional metrics.

The architects of this proposal rely on highly uncertain data, aggressive imputations, and methodological choices that systematically exaggerate inequality trends while ignoring the institutional drivers of human flourishing. Treating inequality as a planetary emergency requiring technocratic global management risks diverting attention from the real engines of development and from the remarkable gains the world has already achieved. Instead of constructing a new bureaucracy to police distributional outcomes, we should focus on the proven path: strengthening the rule of law, expanding economic freedom, and enabling broad-based growth that lifts the poor in absolute terms.

“…the proposal itself suffers from several analytical flaws that make its conclusions difficult to take seriously.”

IMO you are giving it more credence than it deserves by taking it seriously at face value.

It is just another proposal by elite leftists designed for the fundamental purpose of justifying and delivering authoritarian political power to leftists.

Which - whatever the intentions for it when it was first created - is exactly what the IPCC is today.

“Considering the evidence, the call for an International Inequality Panel modeled on the IPCC rests on a fundamentally flawed diagnosis.“

Except it does not, when you realize that its purpose is to help attain political power for leftists.

Surely you don’t deny that the IPCC has been tremendously helpful to the leftist political cause.

P.S. my objections to how you frame the piece notwithstanding, you’ve got some very good data and make quite good points within.

Sadly, leftists like Piketty et al disbelieve and/or willfully ignore that your statement “For the poorest in society, [societal] income growth is the dominant driver of living standards” is essentially true, at least for modern roughly capitalist societies.

I didn't see any consideration of changes by age. Most that I have seen say there is good mobility between age brackets, that people who are low this year may be high next year, and vice versa. Also, most young people begin with little wealth and accumulate more as they grow older.

I remember well my first encounter with Piketty's cherry picked data, which seemed like fraud to me. Seems he hasn't changed much.