The Long Poverty Decline: Before and After the War on Poverty

A new paper from Richard Burkhauser, Kevin Corinth and colleagues gives us something rare in the poverty literature: clean historical measurement that actually lets us ask the obvious question. Did Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty mark a decisive break in America’s fight against destitution? Or did the big decline in poverty mostly happen before the Great Society arrived, driven not by wealth transfers but by market income?

This new paper finds that the War on Poverty changed the how of poverty reduction (more transfers, more dependency), but it didn’t accelerate the how much. In fact, poverty decreased more before 1963 than after. Below I unpack what the paper does, what it proves, and what it should mean for anyone who cares about liberty, work and sustainable anti-poverty policy.

Comparing apples to apples

A perennial problem in poverty debates is apples-to-oranges measurement. Official statistics historically ignore taxes, in-kind benefits, employer-paid health insurance and other nonwage resources. That makes pre-1964 numbers look worse than they were and post-1964 numbers look better, or at least different, in ways that aren’t comparable.

Burkhauser and Corinth close that gap by building a post-tax, post-transfer “full income” measure extending back to 1939 by carefully imputing taxes, transfers, perquisites and (where available) employer health coverage into the 1940, 1950, and 1960 censuses. The authors then link those imputations to the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplements (CPS ASEC) series already used in modern full-income work.

In short, they create a consistent income yardstick that runs from 1939 through 2023. With consistent measurement, we can finally compare the periods before and after the War on Poverty with fewer methodological excuses.

The headline numbers

Using a consistent post-tax, post-transfer measure, the authors find:

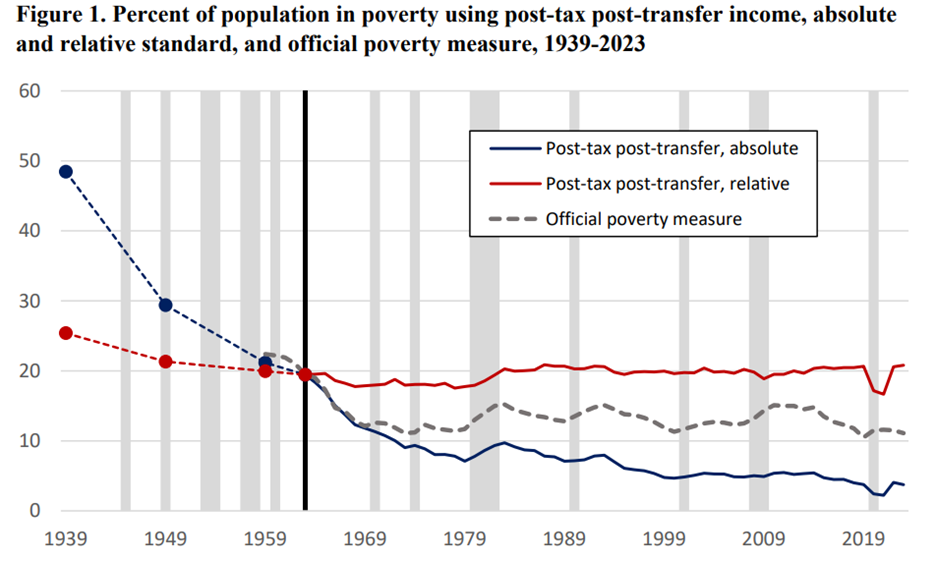

· Absolute poverty fell from 48.5% in 1939 to 19.5% in 1963—a 29-percentage-point decline in just 24 years (see the blue line in Figure 1 below).

· Poverty fell again from 1963 to 2023, but only by 15.7 percentage points, reaching 3.7% in 2023.

· If the market value of health insurance is included in income measures, the overall 1939 to 2023 decline is even larger, dropping to just 1.6% in 2023.

Crucially, when the authors hold the starting poverty rate constant (so the comparison isn’t biased by vastly different baselines), the 24 years immediately before 1963 improved faster than the first 24 years after it. In other words, the greatest era of poverty reduction came before the War on Poverty.

The poverty reduction mechanism

From 1939 to 1959, market income poverty (i.e., a measure that ignores transfers and taxes) fell by roughly 26 percentage points: nearly the entire post-tax, post-transfer decline for working-age adults and children in that era. Only 2-3% of working-age adults depended on government for at least half their income in the pre-1964 years.

By contrast, from roughly 1967 to 2023, market income poverty hardly budged overall (a small, approximately 4-percentage-point reduction), while post-tax, post-transfer poverty fell much more, meaning transfers filled the gap in poverty reduction that market incomes stopped filling. Dependency rates among working-age adults rose to 7-15% in the modern era (with black working-age dependency peaking much higher in some years). In this context, “dependency” means that a majority of household income comes from government transfers rather than earnings or other market income.

Before the War on Poverty, rising wages, employment and the broad postwar expansion of productive opportunity pulled people out of poverty. After the War, transfers (plus slower market income growth for lower incomes) accounted for a much larger share of measured poverty reduction.

The paper also shows that black Americans and children saw massive absolute poverty reductions before 1964. Black poverty fell from 84.1% in 1939 to 50.6% in 1963; black child poverty fell even more sharply. These gains were driven principally by market income growth, urbanization, rising labor force participation and expanding employment opportunities, not by an expanded transfer state.

Relative poverty tells a different story

If we use a relative poverty line (a threshold that rises with median income), progress is far less dramatic. Relative poverty fell modestly before 1963 and has not improved since. That’s important because modern political rhetoric often cares about relative standing, not absolute material deprivation. Transfers can raise absolute resources for the poor, but they do not easily change the structure that creates relative inequality: differences in skills, employment, family structure and productivity.

What this means for policy

1) For lasting poverty reduction, growth beats transfers. The 1939–1963 story is one of rising market incomes across the income distribution. Policies that encourage capital formation, remove barriers to work and widen opportunity will do more to reduce poverty in the long run than adding layers of permanent income replacement.

2) Transfers are not neutral. They help consumption in the short run, but expanded transfers in the post-1963 period raised dependency rates and, at least for a while, coincided with stagnation in market income poverty. That tradeoff matters for social norms, intergenerational mobility and fiscal sustainability.

3) Program design is incredibly important. One government safety-net policy that actually helped spur market incomes was the 1990s welfare-to-work reforms: Market income poverty fell sharply for children and working-age adults in that period. That’s a reminder that safety nets designed to reward work (or to be conditional on labor-force participation) can avoid the dependency trap.

4) Economists should use honest measurements. We need to include full-income accounting, taxes, transfers and employer benefits when evaluating policy. The official poverty rate, while useful in some contexts, is a bad historical comparator by itself.

There’s an old liberal hope, voiced by Lyndon Johnson, that society could “develop and use [people’s] capacities” rather than simply “support people.” The Burkhauser-Corinth paper shows that, historically, economic development did exactly that for millions before the full modern safety net existed. Transfers have been crucial to reduce measurable hardship, but they were not the engine that drove the 20th century’s greatest antipoverty gains.

If the goal is durable escape from poverty, start with the economy: policies that expand jobs, skills and the social institutions that make work pay. Use targeted transfers to smooth shocks, not to substitute for careers. That’s not just a policy preference; it’s what the long history of American poverty reduction appears to tell us.