The Reinhart-Rogoff Excel Error Debate Resurfaces

Over the weekend, a series of viral posts on X resurrected a familiar claim: that an Excel coding error in Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff’s seminal 2010 paper “Growth in a Time of Debt” invalidated the paper’s empirical case that high public debt reduces economic growth. The posts repeated the now well-known point that five countries were inadvertently excluded from a key average calculation. Once corrected, the reported average growth rate for countries with debt-to-GDP ratios above 90% rises from -0.1% to +2.2%. The X poster’s implication is that Reinhart and Rogoff’s debt-growth relationship was a statistical artifact and that subsequent fiscal consolidation was premised on a spreadsheet mistake. This interpretation is incomplete and misleading.

What the Herndon-Ash-Pollin Replication Established

Thomas Herndon, Michael Ash and Robert Pollin (2013) critiqued the Reinhart-Rogoff analysis, identifying three problems: a coding error, unconventional weighting procedures and selective data exclusions. Correcting these problems raised the average growth rate for countries with debt ratios above 90% to 2.2%. This revision eliminated the dramatic “growth cliff” result emphasized in the original paper.

The corrected results did not imply that public debt is unrelated to growth, however. Even in the replication study, growth rates decline as debt ratios rise. What disappears is the claim of a sharp and universal nonlinear threshold at 90% of GDP. What remains is a negative association between high debt and economic growth, with some evidence of nonlinearity that is more gradual and context-dependent. The bar chart below shows the corrected findings of the replicated study.

The replication altered the magnitude and shape of the relationship at very high debt levels, but it did not overturn the broader finding that higher debt burdens are associated with weaker growth performance.

Evidence from the Post-2013 Literature

In a 2020 literature review, “Debt and Growth: A Decade of Studies,” my colleague Veronique de Rugy and I examined the body of research that followed the Reinhart-Rogoff controversy. The empirical findings were heterogeneous with respect to a specific 90% threshold, but the overall pattern was consistent: Large public debt burdens tend to reduce economic growth, and in many cases the adverse effects intensify as debt rises.

A 2021 review in the Cato Journal reached a similar conclusion. While evidence for a common nonlinear threshold was mixed, the preponderance of studies continued to find that growth declines as debt ratios increase. Where nonlinearities are present, they appear to depend on country characteristics such as institutional quality, level of development and macroeconomic credibility.

The more recent literature reinforces this view. In my latest survey, I compile 80 empirical studies published between 2010 and 2025. Seventy-two of these appear in peer-reviewed academic journals; the remaining eight are working papers or policy studies from institutions such as the Federal Reserve, the Bank for International Settlements, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. These non-peer-reviewed contributions were included on the basis of methodological rigor and institutional credibility.

Of the 80 studies, 53 attempt to identify a nonlinear debt threshold. Forty-seven report evidence of such a threshold; six do not. Among the 56 studies that provide quantitative estimates of the effects of debt on growth, 54 report negative growth effects associated with higher public debt, while only two find no statistically significant effect.

These results do not support the claim that the debt-growth relationship rests on a spreadsheet error in a single study.

Threshold Estimates and Their Dispersion

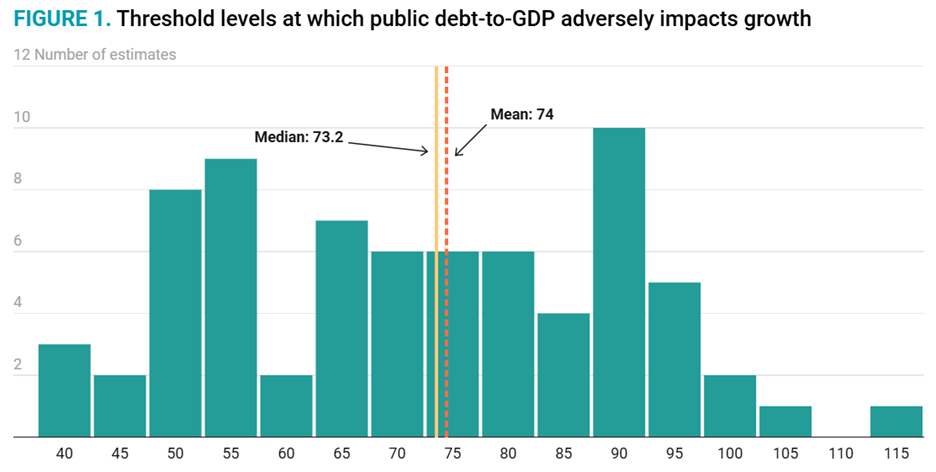

Among the 47 studies in my 2026 survey that report nonlinear threshold effects, the mean estimated threshold level is 74% of GDP and the median is 73%. Restricting attention to advanced economies yields marginally higher figures, with mean and median thresholds of approximately 75% and 76%, respectively. These estimates are broadly consistent with earlier surveys.

Source: The Impact of Public Debt on Economic Growth: What the Empirical Literature Tells Us. Last updated on January 7, 2026. https://www.mercatus.org/research/policy-briefs/impact-public-debt-economic-growth-what-empirical-literature-tells-us

At the same time, the dispersion of threshold estimates is substantial. Reported values range from roughly 50-60% of GDP in some developing-country samples to 70-100% in advanced-economy samples. The evidence therefore suggests that if thresholds exist, they are not universal constants. Rather, they depend on structural characteristics, institutional quality, financial development and policy credibility.

The absence of a single global tipping point does not imply the absence of economically meaningful effects; it implies heterogeneity.

Quantitative Magnitudes

Among the 56 studies in my 2026 survey that estimate the marginal effect of public debt on growth, I collect 197 estimates with reported confidence intervals and conduct a meta-analysis. The central estimate indicates that a one-percentage-point increase in the public debt-to-GDP ratio reduces real GDP growth by approximately 3.3 basis points.

While modest in isolation, such effects compound over time. Sustained increases in debt ratios of 20-30 percentage points, well within the experience of many advanced economies over the past two decades, imply materially lower long-run income levels relative to counterfactual paths.

On the Use of the Paper in Policy Debate

It is often argued that Reinhart and Rogoff’s original findings were “widely cited” to justify postcrisis austerity after the Great Recession. Even if one grants that the paper influenced public debate, two points are worth emphasizing. First, fiscal consolidation decisions in Europe were shaped by sovereign risk, bond market pressures and institutional constraints within the euro area, not solely by one empirical study. Second, the subsequent literature has not vindicated the view that debt is irrelevant for growth. It has refined, qualified and contextualized the relationship.

The Excel error was real and appropriately corrected. But the broader empirical research program that followed, spanning more than a decade, has consistently found that higher public debt is associated with weaker economic performance.

The True Lesson of Reinhart-Rogoff

The resurgence of the Reinhart-Rogoff spreadsheet episode on social media presents a misleading narrative: that a coding error invalidated the economic case against excessive public debt. The accumulated evidence does not support that conclusion.

The post-2013 literature indicates that while there may be no universal 90% threshold, higher public debt ratios are generally associated with lower economic growth, and in many cases the adverse effects intensify beyond country-specific threshold ranges. Estimates of these thresholds cluster in the 60-100% range, with central tendencies in the mid-70s for advanced economies. Meta-analytic evidence suggests that incremental increases in debt reduce growth over time, and the cumulative effect can become substantial.

The appropriate lesson from the Reinhart-Rogoff episode is not that debt does not matter. It is that empirical claims should be replicated, methods scrutinized and conclusions refined in light of new evidence. On that standard, the debt-growth literature has evolved in a way consistent with cumulative scientific inquiry, not its repudiation.