Who’s Afraid of Tariffs? Investors, Especially in “Red” America

Huijun Yan and Randall Morck have a sharp new NBER working paper out: “Who’s Afraid of Tariffs? The Geographic Distribution of Fear and Loss.” It uses the April 2025 tariff shock as a natural experiment to ask a simple, uncomfortable question: Did the promised “re-industrialization” actually boost investor confidence where it was politically intended to—in more conservative, more blue-collar regions of America? The authors find that fear went up everywhere, and losses were larger in redder, more educated, more populous counties.

On April 2, 2025, President Trump declared “Liberation Day” and announced sweeping tariffs, a universal baseline plus “reciprocal” add-ons keyed to bilateral goods deficits for certain countries. Markets promptly tanked. Within days the administration partially paused implementation, and prices rebounded. Yan and Morck call that April 3–8 period, when the tariffs were fully implemented, the Liberation window. The authors’ analysis of this window shows a spike in fear and uncertainty measures, right when tariffs hit and again when they were paused. That’s exactly what you’d expect if the tariffs’ formula and magnitudes surprised markets.

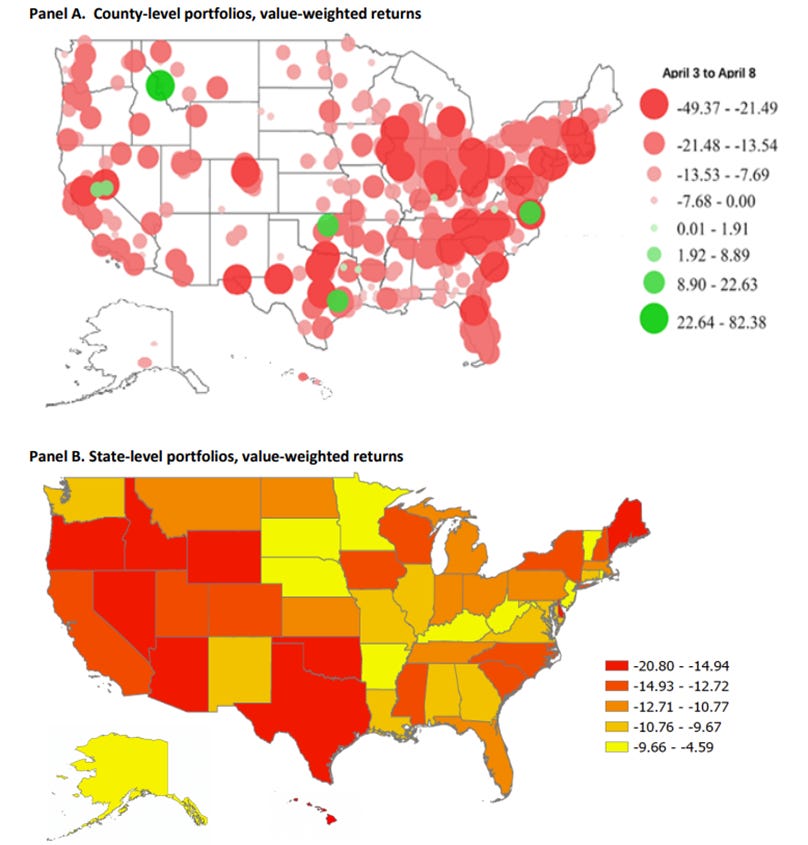

The clever part of Yan and Morck’s paper is geographic. The authors build county-level portfolios from public firms’ headquarters locations (509 counties with at least one HQ). They then sort and regress those returns on county traits: political “redness” (Republican votes per Democrat vote in 2024), education mix (blue-collar versus white-collar, proxied by the ratio of residents with ≤high school to ≥BA), population, number of HQs, and proximity to borders/coasts. Think of it as testing the campaign claim that tariffs would shift the center of economic gravity back toward less educated, more conservative, inland America. The figure from their paper below shows county- and state-level value-weighted returns during the Liberation window. The darkest red areas indicate the heaviest losses.

Figure 1. Geographic Distribution of Losses, Liberation Window (Apr 3-8, 2025)

Notable Findings

1) The market read Liberation Day as a large, negative and unexpected shock. Across major U.S. indices, returns fell double digits in the Liberation window; fear and uncertainty jumped in lockstep; then prices recovered when policy paused. That “surprise–fear–pause–relief” shape is hard to reconcile with the idea that investors anticipated, understood and welcomed the tariff regime. Other teams using different lenses, macro models, state-level trade frameworks and high-frequency identification similarly conclude that tariffs are contractionary and confidence-sapping.

2) Losses were bigger in redder places. Conditioning on population and firm counts, portfolios of firms headquartered in politically redder counties fell more in the Liberation window, both in total returns and abnormal returns (i.e., those beyond what you’d predict from the broad market move). The effect is economically meaningful: Moving from a low-red to a high-red county adds several percentage points of extra loss over those few trading days. That is not the pattern you’d expect if investors believed tariffs would immediately tilt profit opportunities toward the Republican heartland.

3) More blue-collar counties sometimes lost less, but that’s not the win you think it is. In the earlier “First Trade War” window (Jan–Mar 2025) of Canada/Mexico/EU/China escalations, portfolios tied to more blue-collar counties did lose a bit less. The authors interpret this guardedly: part firm mix, part leverage/industry composition, and part lower comovement with the market. Crucially, once you focus on abnormal returns in the Liberation window—the cleanest read on “new information” about prospects—the political redness effect remains, while blue-collar insulation largely fades.

Additional Nuances

Industry mix matters but doesn’t change the conclusion. Adding industry fixed effects raises R² and trims coefficient magnitudes, which means some of the “red county underperformance” is channeled through industries that are more concentrated in redder places. Even so, industries with stronger ties to more conservative or more blue-collar counties still posted more negative abnormal returns in the Liberation window—that is, losses beyond what the broad market drop would imply.

Borders and coasts aren’t first-order drivers. Proximity to Canada, Mexico or salt water isn’t consistently significant once you control for politics, education and urbanization. The fear wasn’t just because “supply-chain-exposed coastal firms got hit”; it was wider and had more to do with political economy.

Firm size affects outcomes in different ways. Smaller firms were hit harder during the Jan–Mar episode, but the Liberation window saw relatively larger losses among bigger firms (in raw returns), though size was less predictive for abnormal returns. That’s consistent with the Liberation formula shocking expectations in a way not explained simply by standard small-cap fragility—that is, the common tendency of smaller firms to be more vulnerable to shocks because they have less financial resilience and market access than larger firms.

Key Takeaways

First, tariffs didn’t deliver confidence dividends to the places they were purported to help. If anything, Liberation Day concentrated more fear in redder counties, the very regions that had been promised protection from global competition. Markets collectively concluded that higher, more discretionary, more politically instrumented trade barriers reduce expected output and productivity and inject uncertainty—exactly what the empirical literature has been telling us for years.

Second, the “reciprocal-by-deficit” tariff design amplified uncertainty. Investors don’t price policy slogans; they price budget constraints and production functions. A formula that ties tariff rates to bilateral goods gaps rather than to actual partner policies (i.e., tariffs) is a recipe for volatility: hard to forecast, easy to escalate and orthogonal to the accounting identities that balance goods with services and capital flows. That tariff design choice, combined with abrupt decree-driven implementation, helped turn a policy pitch into a fear shock.

Third, if your goal is to raise durable investment in tradables in the interior of the U.S., tariffs are a blunt and counterproductive tool. You don’t get capital deepening by injecting policy risk and disrupting supply networks. You get it by lowering the user cost of capital and making the rules stable: full expensing or neutral cost recovery, fewer discretionary waivers, cleaner permitting, better trade facilitation and more predictable border administration. The model-based papers published since April similarly found that tariffs shrink real income and employment overall.

The findings of Yan and Morck’s study are another nail in the coffin of “black-hole tariff” economics. Protectionist policies can deliver private gains to the best-lobbied incumbents, but the general equilibrium (especially under a capricious formula) erodes expectations, swells risk premia and torpedoes the very regions it purports to champion. If policymakers want to actually help Republican, blue-collar America, they should retire the tariff talk and get serious about supply-side liberalization at home and predictable, rules-based trade abroad.

Uhhhh… so what?

Is it the slightest bit surprising that during the period of maximum uncertainty, people who are at least generally aware of what’s going on but less well off financially - i.e. the current GOP base - would be more worried about the impact than those who are either much better off, or dependent on government, disproportionately not employed and not paying as much attention to current events - i.e. the current Dem base?

Looking at “red HQs” and primarily blue, extremely well off investors calculating that manufacturers in the midddle of the country might do worse in a recession than, say, service companies on the coasts is also hardly surprising.

For the record, I applaud 20% - 35% of what Trump has done in this whole area - most notably in getting so many other countries to reduce their tariffs and NTBs - and deride 30% - 50% as bad for the economy and the country.

But this “finding” re: who was most worried about what is just not meaningful.