Why Are Interest Rates So High? It’s Bad Fiscal Policy

CBO Models Underestimate the Fiscal Threat of Rising Debt

Throughout the 2010s, the persistence of low interest rates lulled many economists and policymakers into believing low rates were the new normal. As recently as November 2020, former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers and Harvard economist Jason Furman noted that “markets suggest that five years out there is a 72 percent chance that nominal rates will be at their current level of effectively zero or even negative.”

Fast forward to today: the 10-year Treasury yield has been comfortably above 4% for almost 3 years. The common explanations point to inflation, Fed tightening, and global economic uncertainty. But there’s another force at work that’s getting too little attention: the mounting burden of public debt.

In a new policy brief, I examine just how much rising U.S. public debt is pushing long-term interest rates higher—and why the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) is underestimating the effect.

20 Years of Studying Link Between Debt and Interest Rates

There’s a solid body of economic literature showing that when government debt rises, so do interest rates. The basic idea is straightforward: higher government borrowing competes with private investment for capital, which pushes up the price of borrowing.

Empirical studies over the past 20 years consistently find that a 1 percentage point increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio raises long-term interest rates by about 3 to 5 basis points (bps). As table 1 shows, more recent estimates tend to center around 4 bps.

Yet despite this growing consensus, the CBO recently lowered its own estimate of the debt effect—from 2.5 to 2 bps. That’s not a minor tweak; it’s a substantial departure from where most of the evidence points.

Measuring the Link

To test how realistic the CBO’s assumption is, I analyzed quarterly data from 1985 to 2024, accounting for key structural factors that affect long-term interest rates. These factors included inflation expectations, real GDP growth, demographics, and foreign demand for U.S. debt.

The results (table 2) are telling.

· Baseline estimate: A 1-point increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio raises the 10-year Treasury yield by 4.6 bps.

· After removing outlier data (table 3), the effect grows to 5.5 bps.

· When lagged by one year (table 4), the effect exceeds 6 bps, suggesting a delayed market response to rising debt.

In short, the CBO’s 2 bps assumption isn’t just a little low—it’s less than half the actual observed effect.

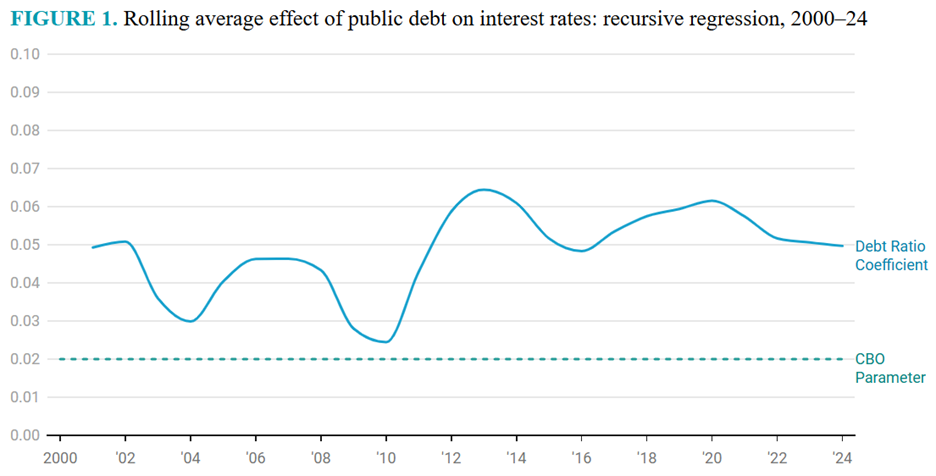

Another way to measure the impact of public debt on interest rates over time is by using recursive regression analysis. Figure 1 below illustrates the results of such an analysis, with the green dashed line representing the CBO’s 2 basis point debt impact parameter. This line is included to show how conservative the CBO estimate is relative to the actual relationship between debt and interest rates over time. The rolling average coefficient shows how the debt impact on interest rates typically fluctuates over time between about 3 and 6 bps.

Structural Shifts in Interest Rate Dynamics

It’s important to put this in context. For decades, structural factors were pushing rates down. Aging populations, a strong foreign appetite for Treasuries, and declining inflation premiums all contributed to the low-rate environment of the 1990s and 2000s.

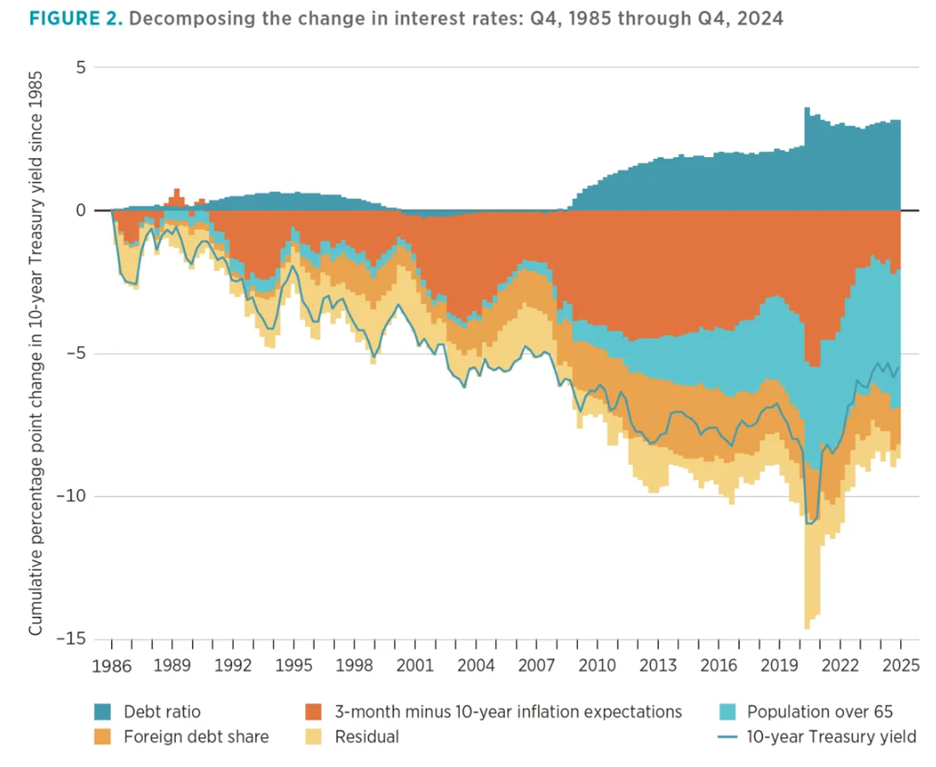

But that dynamic has shifted. Since 2012, rising debt, declining foreign demand, and a resurging term premium have overtaken those downward forces. Figure 2 decomposes the change in interest rates over time by structural factors.

My analysis finds that since the Great Financial Crisis, all else equal, the growing debt ratio has raised rates by roughly 3 percentage points. Foreign holdings of U.S. debt have declined sharply since about 2014, contributing another 1.4 points. The term premium has added 2.5 points, reflecting growing investor concern over fiscal sustainability.

In total, these three upward pressures have counteracted downward factors, reversing decades of rate declines.

Accurate Assumptions Matter for Fiscal Policy

The CBO’s long-term budget projections assume that the 10-year Treasury yield will stabilize around 3.8% by 2055. But if the debt impact is closer to reality, then we’re looking at yields closer to 5% to 5.5%, all else equal.

That difference may seem small, but it has massive implications for the federal budget. Higher interest rates mean higher debt servicing costs, larger deficits, more borrowing, and a greater risk of a fiscal doom loop.

If policymakers are making trillion-dollar decisions based on faulty interest-rate forecasts, they’re flying blind.

Read the full policy brief here: https://www.mercatus.org/research/policy-briefs/impact-public-debt-interest-rates.