Public Debt, Treasury Yields and Mortgages: Implications for Housing Affordability

How Reckless Spending Pushes Housing Ownership Out of Reach

The issue of housing affordability has become increasingly pressing in recent years with rising home prices and mortgage rates squeezing household budgets and making homeownership a distant possibility for many young families. While numerous factors contribute to this challenge, one is often overlooked: the impact of rising public debt.

Following the global financial crisis and further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, public debt levels have surged to historic highs. This persistent growth in debt raises concerns about potential macroeconomic consequences, including the impact debt can have on interest rates and, consequently, the housing market.

In particular, changes in public debt affect 10-year Treasury yields, which serve as a key benchmark for mortgage rates. As the supply of government bonds increases to finance growing debt, upward pressure is exerted on yields. These yields, in turn, have a strong influence on mortgage rates, as lenders typically price mortgages based on a spread over the risk-free rate represented by Treasury yields. By understanding the transmission mechanism from public debt to housing costs, policymakers can implement more effective strategies to promote housing affordability and financial well-being.

The Trajectory of Public Debt and the Impact on Treasury Yields

Over the past two decades, public debt as a share of GDP has grown by roughly 30 percentage points every decade. Unfortunately, this trend appears set to continue. According to the latest Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projections, debt held by the public is forecast to rise by 21 percentage points in the coming decade, from 98 percent in 2024 to 119 percent in 2035. Using current law as a baseline, the additional cost of extending the expiring provisions of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) would push the 2035 public debt ratio above 130 percent. In sum, the public debt ratio is currently forecast to grow by about 30 percentage points in the coming decade. Beyond that timeframe, Social Security and Medicare trust fund solvency (expected in 2035 and 2036, respectively) will likely place further upward pressure on the debt ratio.

The subsequent growing burden of public debt raises long-term interest rates. The decline in private investment resulting from debt crowd out reduces the amount of capital per worker and further increases interest rates and the return on capital over time. High and growing public debt levels inflate interest rate yields by crowding out private investment, raising the credit risk premia and increasing the risk of inflation (Elmendorf and Mankiw, 1999; Codogno et al. 2003; Cochrane, 2023).1 The bulk of empirical literature finds that each percentage-point increase in the debt ratio raises long-term interest rates by 3 to 5 basis points (bps).2 Using 4 bps as a benchmark impact parameter, we can estimate that, had the debt ratio remained at 2005 levels (35 percent), then 10-year Treasury yields would have been 2.11 percent in January 2025, rather than the actual 4.63 percent.

All other structural factors aside, the projected 30 percentage points increase in the debt ratio will add further upward pressure to Treasury yields amounting to roughly 1.2 additional percentage points in the coming decade. To make matters worse, past structural factors that might have historically mitigated some of the effects of public debt on interest rates are now far less predictable.

Why Higher Treasury Yields Matter for Housing Affordability

Mortgage rates are closely tied to the 10-year Treasury yield as a benchmark because the yield reflects the interest rate that the U.S. government must offer to borrow money for a decade, which is seen as a stable and secure investment. Lenders use this rate as a gauge for setting their own interest rates on long-term loans, including mortgages, because they want to ensure their returns are competitive with government bonds while accounting for the additional risk associated with lending to homebuyers. When Treasury yields rise, lenders typically increase mortgage rates to maintain this balance.

The relationship between Treasury yields and mortgage rates also reflects broader economic conditions. A rise in Treasury yields often signals expectations of higher inflation or a stronger economy, which leads lenders to anticipate higher borrowing costs in the future. As a result, mortgage rates tend to rise in tandem with Treasury yields. Conversely, when Treasury yields fall, mortgage rates usually decrease as well, making borrowing more affordable. Therefore, shifts in the 10-year Treasury yield have a direct impact on the cost of mortgage debt, influencing the affordability of homeownership and the housing market overall.

Using 21 years of data from the Federal Reserve Bank and Freddie Mac, we can review the correlation between 10-year Treasury yields and 30-year mortgages from January 2004 through December 2024. Figure 1 below shows the correlation between these two variables over the 21-year period observed. The R Square is 0.89; meanwhile, R is found to be 0.94, indicating a very strong positive relationship between the two variables.

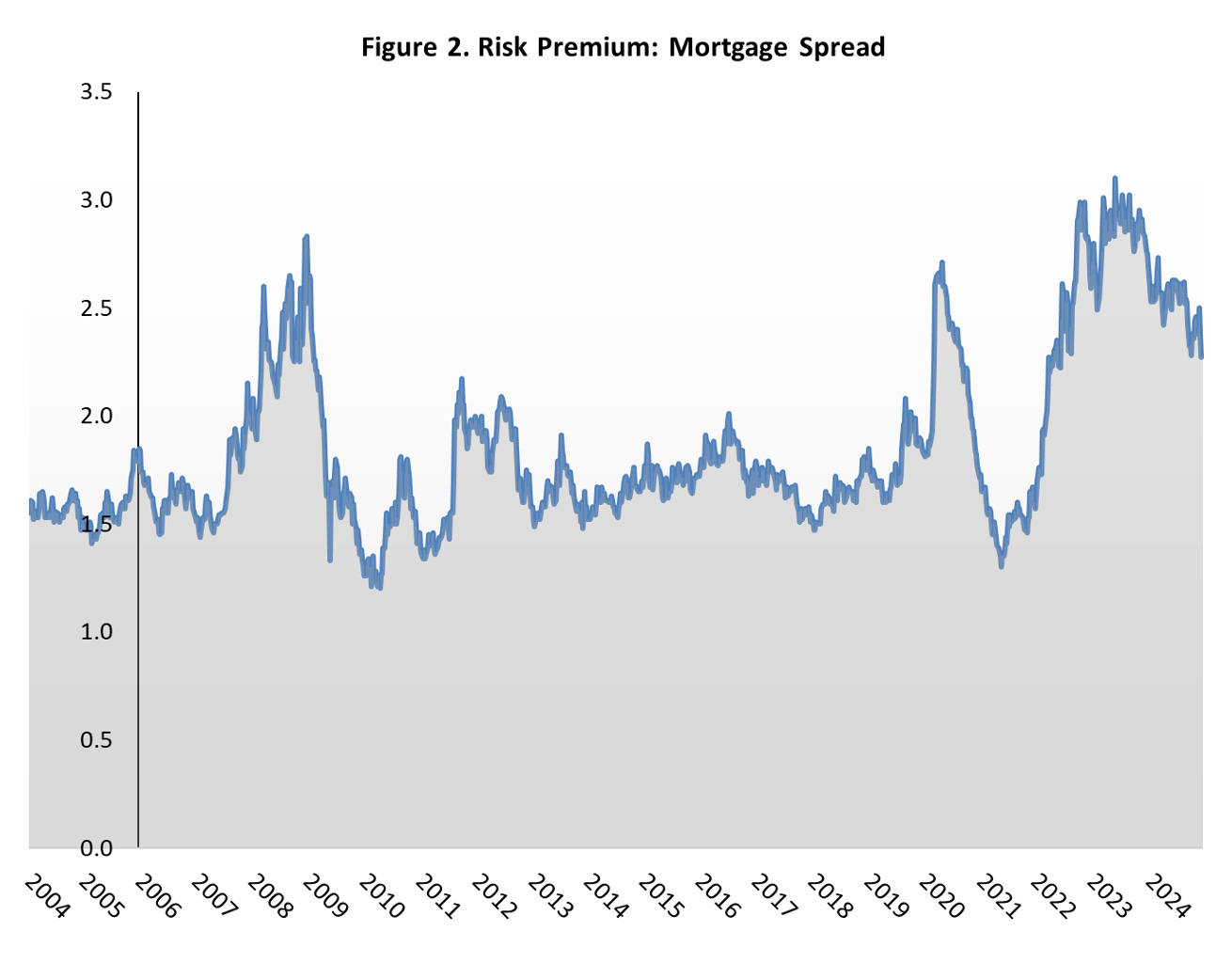

While mortgage lenders use the 10-year Treasury yield as a benchmark in determining the rates they set on mortgages, lenders charge a rate that is notably higher than that of the 10-year Treasury yield. While Treasury yields offer a benchmark, the lender adds a risk premium, for example, the added credit risk of borrowers failing to make payments or the liquidity risk as mortgages are less easily traded than Treasuries. Observing data from 2004 through 2024, the risk premium that lenders charge is typically between 1.5 and 2 percentage points. Figure 2 below shows how the mortgage spread risk premium has fluctuated over time. The mean and median risk premium during this 21-year period was 1.85 and 1.7 respectively. Mortgage spreads tend to be close to 1.5 during stable economic periods and closer to 2.5 during periods of economic stress or elevated inflation.

Performing a simple linear regression analysis yields a coefficient of 1.022 for the 10-year yield, meaning that for each percent point increase in the 10-year Treasury yield, the 30-year mortgage rate is expected to increase by approximately one percentage point. The coefficient is statistically significant. Given the trajectory of public debt and its impact on long-term interest rates, we are unlikely to see the 3 to 4 percent mortgage rates that were the norm between 2010 and 2021. Instead, it is more likely that mortgage rates will be around 5 to 7 percent in the coming years, and absent serious fiscal consolidation, rates could trend higher in the long term.

This dynamic presents a growing challenge for prospective homeowners, particularly younger generations and middle-income families who are already facing affordability constraints. As public debt continues to rise, higher long-term interest rates are a real risk, further diminishing housing affordability.

While this piece focuses specifically on the impact of public debt on homeownership affordability through the Treasury-yield channel, it is important to acknowledge that other factors contribute to the rising cost of housing. Limited housing supply, driven by restrictive zoning laws and burdensome land use regulations, has made it increasingly difficult to build new homes in high-demand areas. Excessive permitting requirements and bureaucratic delays further slow development, driving up construction costs and limiting the availability of new housing. Additionally, a complex web of local, state and federal regulations adds to the cost of both new construction and homeownership, making housing less accessible for many Americans. While these structural issues play a significant role in driving up the cost of housing, the impact of public debt through higher interest rates also has a profound impact on making home ownership less affordable.

To mitigate the negative impact of public debt on mortgage rates, governments should prioritize fiscal consolidation efforts aimed at stabilizing and ultimately reducing debt-to-GDP ratios. This could include responsible spending reductions, pro-growth tax policies and entitlement reforms to address long-term liabilities.

Elmendorf, Douglas W., and N. Gregory Mankiw. "Chapter 25 Government debt." Handbook of Macroeconomics, 1999, 1615-1669; Codogno, L., C. Favero, and A. Missale. "Yield spreads on EMU government bonds." Economic Policy 18, no. 37 (2003), 503-532; Cochrane, John H. The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2023

For a review of empirical literature see: Jack Salmon, “Long-Term Interest Rate Projections and the Federal Debt,” Liberty Lens—An Economics Substack, October 2024